|

From 'Orthodoxy and the World' www.pravmir.com Contemporary Issues Source: The Antiochian Orthodox Christian Archdiocese of North America

Following in every detail all the decrees of the holy Fathers and knowing about the canon, just read, of the one hundred and fifty bishops dearly beloved of God, gathered together under Theodosius the Great, emperor of pious memory in the imperial city of Constantinople, New Rome, we ourselves have also decreed and voted the same things about the prerogatives of the very holy Church of this same Constantinople, New Rome. The Fathers in fact have correctly attributed the prerogatives (which belong) to the see of the most ancient Rome because it was the imperial city. And thus moved by the same reasoning, the one hundred and fifty bishops beloved of God have accorded equal prerogatives to the very holy see of New Rome, justly considering that the city that is honored by the imperial power and the senate and enjoying (within the civil order) the prerogatives equal to those of Rome, the most ancient imperial city, ought to be as elevated as Old Rome in the affairs of the Church, being in the second place after it. Consequently, the metropolitans and they alone of the dioceses of Pontus, Asia and Thrace, as well as the bishops among the barbarians of the aforementioned dioceses, are to be ordained by the previously mentioned very holy see of the very holy Church of Constantinople; that is, each metropolitan of the above-mentioned dioceses is to ordain the bishops of the province along with the fellow bishops of that province as has been provided for in the divine canons. As for the metropolitans of the previously mentioned dioceses, they are to be ordained, as has already been said, by the archbishop of Constantinople, after harmonious elections have taken place according to custom and after the archbishop has been notified.

The issue of the proper interpretation of Canon 28 and its relationship to the so-called “diaspora” is crucial, not only to the Church in North America, but to the relationship of all Orthodox churches worldwide to each other, and to their witness to the world. As Patriarch ALEKSY of Russia has said: “The question of the Orthodox diaspora is one of the most important problems in inter-Orthodox relations. Given its complexity and the fact that it has not been sufficiently regularized, it has introduced serious complications in[to] the relations between Churches and, without a doubt, has diminished the strength of Orthodox witness throughout the contemporary world.” (For more information on the historical background of Canon 28, I recommend the book The Church of the Ancient Councils: The Disciplinary Work of the First Four Ecumenical Councils, by the late Archbishop PETER L’Huillier, published in 1996 by St. Vladimir’s Seminary Press.)

It is my opinion that there are three types of canons: 1) Dogmatic; 2) Contextual; and 3) “Dead” canons. Canon 28 is by no means a “dead” canon, since there is still great controversy over it today, and so many commentaries, both past and present, show how controversial it has been, to say the least. I believe that Canon 28, historically, is a contextual canon and not a dogmatic one; it gave the city of Constantinople certain rights as the New Rome for secular, political reasons because it was the seat of the emperor. At the same time, the Fourth Ecumenical Council considered (Old) Rome to be the first among equals. What does this say to us today? Let us begin by stating that the whole idea today of “Rome,” “New Rome,” and “Third Rome” would be absurd. If we want to give prominence to any city in Christendom, we should give it to Jerusalem, where the history of salvation was accomplished.

The second part of the Canon dealt with the Dioceses of Pontus, Asia and Thrace. Canon 28 gave Constantinople jurisdiction over the metropolitans of the barbarians and those three provinces or dioceses, which today are only Bulgaria, Northeastern Greece and European Turkey.

We can also ask, Is this Canon dealing with a dogmatic issue or a pastoral administrative one? In my opinion it clearly deals with an administrative question. If Antioch or Alexandria had become the seat of imperial power, likely this Canon would have made either of them New Rome. If we were to follow the reasoning of Canon 28, in fact, then Russia could rightfully claim, as it did historically, to be the Third Rome, and the Church of Greece could have made the claim to be the Fourth Rome during the captivity of the Russian Church under Communism.

Given the lack of a new Great Council, common sense would dictate that, with the current captivity of the church in Constantinople (whose indigenous flock totals just a few thousand), there is no reason for Canon 28 and it is no longer relevant today. We do have a problem, however: we have a responsibility to the past and the councils of the past, but there is no Great Council to address this issue. We must therefore explore other solutions.

While the Canon is not relevant to the question of different “Romes,” it is profi table for us to look at its relevance today, especially to the subject of administrative organization in North America. We are well aware of the complex issues regarding the so-called “diaspora” and the desire of our Orthodox people, especially in North America, to have an administratively united church. As you must know, there are basically two interpretations of this Canon that extend back into history. Some claim that this Canon implies that Constantinople has authority over all territories outside the geographical limits of autocephalous churches.

Those on the other side of the argument say that this interpretation is, in fact, misinterpretation. Archbishop PETER in his book, The Church of the Ancient Councils, states that “such interpretation is completely fantastic.” For those holding this view, any autocephalous church can do missionary work outside her boundaries and can grant autocephaly to such missions. Archbishop PAUL of Finland, in summarizing the position of the Orthodox churches, has stated in the reports submitted in 1990 to the Preparatory Commission for the Great and Holy Council that “the Patriarchates of Antioch, Moscow and Romania strongly oppose the authority of Constantinople over the diaspora and [maintain] that the theory remains an anachronism as far from the modern age as the year 451 of the Fourth Ecumenical Council is from the Twentieth Century.”

Patriarch ALEKSY of Russia has stated that it was only in 1921 that Patriarach MELETIOS Metsakis developed a theory of universal jurisdiction for Constantinople. “Historical facts indicate that until the 1920’s the Patriarch of Constantinople did not in fact exercise authority over the whole of the Orthodox diaspora throughout the world, and made no claim to such authority.” The Russian Orthodox Church responded in a letter to the Ecumenical Patriarchate regarding the case of Bishop BASIL (Osborne) as follows: “With respect to Canon 28 of the Council of Chalcedon, it is vital to recall that it concerns only certain provinces, the boundaries of which represent the limits of the authority of the Patriarch of Constantinople over the bishops ‘of the barbarians.’”

We see, then, that the notion that this Canon extends the authority of the throne of Constantinople to all territories that are not part of one or another local church is a novelty, and one not recognized by the Orthodox Church as a whole. This misinterpretation of Canon 28 would extend beyond territorial issues to such things as the claim that a representative of the Patriarchate of Constantinople should chair any Episcopal assembly, anywhere in the world. This claim can extend down to local clergy groups, Pan-Orthodox associations and organizations, and so forth.

In 1961, we in the United States and Canada formed the Standing Conference of Canonical Orthodox Bishops in the Americas (SCOBA). I have been a member of SCOBA since 1966. The misinterpretation of Canon 28 has not been helpful to the work of SCOBA. In my opinion, SCOBA has four major defects. First, the representation of the Orthodox Churches in SCOBA does not reflect reality in North America. Neither the Moscow Patriarchate nor the Russian Orthodox Church Outside of Russia (ROCOR) are represented in SCOBA, while the Ecumenical Patriarchate has four of the nine seats.

Second, the insistence that the Exarch of the Patriarchate of Constantinople must be the President of SCOBA is not what was agreed upon at the beginning. The constitution of SCOBA which has never been amended, provides that there shall be a rotating presidency. Subsequently, at the insistence of the Antiochian Archdiocese, Archbishop SPYRIDON and then Archbishop DEMETRIUS were elected by the SCOBA members after the retirement of the later Archbishop IAKOVOS of thrice-blessed memory.

The third defect of SCOBA is that its decisions are not internally binding. In the 1990 documents before the Preparatory Commission for a Great and Holy Council, in discussing the Western European situation, some autocephalous churches suggested the formation of Episcopal Assemblies whose decisions can be internally binding.

I would like to quote here again from the letter from the Russian Orthodox Church to the Preparatory Commission. The relations between jurisdictions and dioceses to the Mother Churches would remain the same, but in all purely internal matters, which would include education, teaching, the diakonia, Orthodox witness, ecumenical relations on the local level, pastoral practice, the Bishops’ Assembly would serve in joint effort as one whole unite and autonomous in its relationship to the mother church.” This Bishops’ Assembly, for example, would address non-canonical situations in North America such as the infringement of the Patriarchate of Jerusalem in North America with the blessings of the Patriarchate of Constantinople.

A fourth problem with SCOBA, I believe, is the assumption that we are a “diaspora.” On the contrary: the only way to move the cause of Orthodox unity forward in North America is to insist that we are not a “diaspora.” We have been here two hundred years. The late Protopresbytr, John Meyendorff, of blessed memory, states in an essay in his book A Vision of Unity that diaspora is a biblical term and has a perfectly adequate equivalent – “dispersion.” He says later in the same article: “There is no promised land any more except the heavenly Jerusalem.”

Most of the people in my Archdiocese have no intention of returning to their place of origin. This is true even of new immigrants, let alone those of the third or fourth generation. Our people are here to stay, and we are indeed an indigenous church in North America. I believe that the Church in North America is mature enough to take care of herself without any interference from the outside. Those who support an ethnocentric reading of Canon 28 and insist that unity on a national basis cannot be discussed, then, are naïve and bury their heads in the sand. While they may delight in holding lectures and conferences on the environment, the witness and mission of the church is ignored. The Orthodox principle is not to organize the church based on ethnicity, but, in the modern world, upon the nation-state. Ironically enough, when ethnic ecclesiology began to flourish and prosper in the nineteenth century, it was the Pan-Orthodox Synod of Constantinople itself that condemned ecclesiological ethno-phyletism as heresy in 1872. During our Archdiocese Convention last July in Montreal, Canada, I shared with my clergy and laity what I said on the subject to my brother bishops at the Archdiocesan Synod Meeting on May 31, 2007, and I summarize my thoughts in what follows. Since 1966, I have lived with two obsessions: 1) The unity of our Archdiocese; and 2) Orthodox Unity in North America. Where are we now in regard to this latter unity? Unfortunately, the Once Holy Catholic and Apostolic Church in North America is now divided into more than fifteen jurisdictions based on ethnicity, contrary to the decisions of the Ecumenical Councils. Our canons clearly state that we cannot have more than one bishop over the same territory, and one metropolitan over the same metropolis. I regret to tell you that we Orthodox are violating this important ecclesiological principle in North America, South America, Europe and Australia. In New York, for example, we have more than ten Orthodox bishops over the same city and the same territory. I can say the same thing about other cities and territories in North America.

We are not alone; the same thing has happened in Paris, France. There are six co-existing Orthodox Bishops with overlapping ecclesiological jurisdictions. In my opinion and in the opinion of Orthodox canonists, this is ecclesiological ethno-phyletism. This is heretical. How can we condemn ethno-phyletism as a heresy in 1872 and still practice the same thing in the twenty-first century here in North America? When I lived in Damascus, Syria, and Beirut, Lebanon, in the early 1950s, there were large Greek Orthodox and Russian Orthodox communities there, but they were not under the Archbishop of Athens or the Patriarchate of Moscow, but under the omophorions of the Antiochian local bishops. Due to wars and social upheaval, we now have a large Lebanese community in Athens, Greece, and they are under the omophorion of the Archbishop of Athens. They do not have a separate jurisdiction just because they are Lebanese Orthodox.

Archimandrite Gregorios Papathomas, a professor of Canon Law and Dean of St. Sergius Theological Institute in Paris, France, wrote, “The defining criterion of an ecclesiastical body has been its location. It has never been nationality, race, culture, ritual or confession”. In First Corinthians (1:2) St. Paul writes, “To the Church of God which is at Corinth…” and again in Second Corinthians he writes, “To the Church of God which is at Corinth….” He writes to the Galatians, “To the Church of Galacia….” (1:2). We learn from the Apostles and the Fathers that the church is one church, one and the same church, the body of Christ, found in Antioch, Jerusalem, Alexandria, Constantinople, Greece, Rome, Russia, and so forth. Based on all of this, it is simply wrong to call the church Russian or Greek or American, because the church, in essence, transcends nationalism, race and culture. Here in North America we distort Orthodox ecclesiology by our ethnic jurisdictions.

The twenty-first century has dawned upon us. What, then, is to be our response to the challenge of Orthodox unity in North America? SCOBA was established in 1961; some of its founders were the late Archbishop IAKOVOS and the late Metropolitan ANTONY Bashir. May their souls rest in peace. Under “Objectives” in Paragraph I, Section C, the original constitution of SCOBA, adopted January 24, 1961, states that “the purpose of the conference is the consideration and resolution of common ecclesiastical problems, the coordination of efforts in matters of common concern to Orthodoxy, and the strengthening of Orthodox unity.” Last year, between October 3 and 6, SCOBA invited all canonical Orthodox Bishops to meet in Chicago, Illinois, to discuss common Orthodox problems. The communiqué issued on October 5, 2006, did not mention a word about Orthodox unity in America.

Again in November, 2006, a meeting of Inter-Orthodox priests met in Brookline, Massachusetts. A draft statement dated January 22, 2007, was circulated and not a word about Orthodox unity in North America was mentioned. I am convinced that serious attempts are being made, by some hierarchs in North America and abroad, to sweep the whole question of Orthodox unity, in this hemisphere, under the rug. After the Brookline encounter, one of my Antiochian clergy wrote to me the following: “Two of the Greek priests gave very strong talks on unity. We did decide, however, that given the landscape, we would use the word ‘cooperation’ and not ‘unity’ in our printed records.” This statement, my friends, speaks for itself.

I believe that an Ecumenical Council would be very difficult at this time. It would probably cause a division, or numerous divisions in the Church, and this would counter-productive. After all, if an issue such as changing the calendar causes splits and division, imagine what would happen if we were to discuss more serious issues. Fortunately or unfortunately, we no longer have the Byzantine emperor to enforce decisions that such a council can make.

An an alternative, I propose the formation of an Inter-Orthodox commission, located some place like Geneva, Switzerland, on which each autocephalous church and each self-ruled church would have a permanent representative. To this commission they would bring issues and problems to be discussed on behalf of the mother churches, and they would deal with specific Orthodox problems throughout the world. The decisions of the commission would be submitted to all mother churches for action.

With all the obstacles we face, have we reached a dead end? No, with the All-Holy Spirit working in the Church, there are no dead ends. I am sure that thousands of Orthodox clergy and hundreds of thousands of Orthodox laity in North America are deeply committed to Orthodox unity. We Orthodox must put our house in order, if we want to have a serious Orthodox mission in North America. This unity will begin with our clergy and laity, on the local level. My generation is slowly, but surely, fading away. It is up to you and our younger generation to carry the torch and to make the light of a unified Orthodoxy shine on this continent and everywhere.

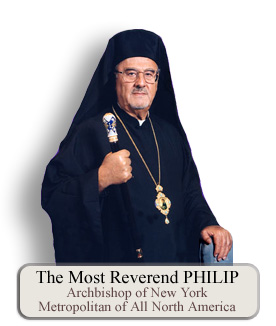

Metropolitan PHILIP’s talk was part of the Conference of the Fellowship of St. Alban and St. Sergius, held at St. Vladimir’s Seminary, June 4-8, 2008.

This article originally appeared in THE WORD Vol. 53 No. 1, January 2009 © Copyright 2004 by 'Orthodoxy and the World' www.pravmir.com |