Source: "Orthodox Canada": A Journal of Orthodox Christianity

I would snicker as a child when my grandfather would reuse envelopes. Coming across some dry wit or ancestral connection in a country newspaper, Grandad would clip the article, and fix it securely with a note inside a recycled brown bank mailer, stuck fast with a yellowed piece of scotch tape.

Postal machines would no doubt have hated my grandfather for his inefficient method of mailing, but I'm not sure he ever met a postal machine. He stopped at the village post office, bought his stamps, and had every new letter hand cancelled on the spot. The machines may not have been his friends, but everyone at the post office knew him by name.

As a farmer, and the son of a UFO supporter (the United Farmers of Ontario - the political voice of rural people during the Depression), Grandad was more comfortable on a tractor than in a car, and much more comfortable in a peach field than in front of the television. He laughed at the idea that people started work at nine in the morning - the day is half gone, he would say. He was in bed soon after sundown every night. (Imagine the impact on energy consumption if all the lights went off at 9pm today).

|

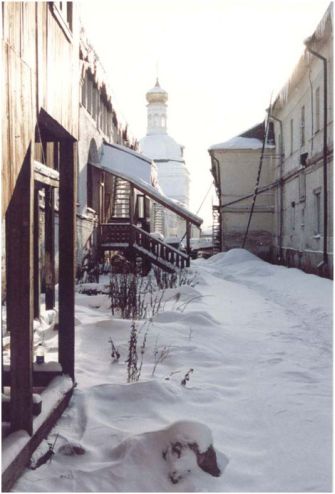

| Photo: Inna Boyko, http://photo.orthodoxy.ru |

One could even tell from a mile away his nighttime routine: two lights on in the dark farmhouse meant he was sitting in his chair in the living room, reading something like the Farmer's Almanac, the Saint Catherine's Standard, or This England; one light on meant he was in his room, saying his prayers. No lights on meant the day was done: don't call him, because he often wouldn't pick up the phone. That was daytime business: there's no sense burning a light at night for that.

Grandad drove the same car for twenty years. It was always clean and ready for church on Sunday morning, so he could arrive early to ring the bell - a hand-rung bell on an old rope pulley. When the car became too old for regular use, he either turned it over for farm use, or passed it on to someone who needed it.

For my Grandad, six days each week meant work. Although he had only an hour or two each day of recreational time, he was well-read in current events, politics, and spiritual and religious matters, which he discussed at family meals three times each day. He did not work on Sundays, unless there was some emergency, which only happened once in a blue moon, not every week. The word "emergency" and "crisis" actually meant something to my grandfather.

Grandad did not ever use the word recycle: he just did it. To him a footprint was something you made with your boot in the mud, while you worked outside the barn. Global warming was something that happened in the summertime, and which called for longer afternoon breaks and lemonade for guests. Pollution was something an irresponsible young man did to himself with a bottle of scotch, and green was the colour of his overalls, not his politics or his spirituality. He didn't buy local goods because the planet needed him to do so: he just liked his neighbours, and they liked him.

Today as we read about Orthodox faithful and hierarchs trying to share the environmental "side" of Orthodox Christianity, I am often reminded of my grandfather. Although he was not an Orthodox Christian, his views on environmentalism were more Orthodox than many contemporary writers in the Church. Like the Church Fathers, he would have seen our environmental crisis as a logical consequence of the fall, not the mechanism for the Apocalypse. He would have told us city folks to simplify our lives, to stop listening to fancy writers who go on lecture tours, to live quietly, to say our prayers, and to never draw attention to ourselves. He would have shaken his head over church leaders jumping on the environmental bandwagon.

I remember a time (I think I was about nine years old) when Grandad wrote away to a mail order company who sold something they called fruit leather (what later came to be known as a fruit roll-up, after they added all the sugar). I think he hated the idea of handing his grandchildren loads of candy. He didn't do any of this as a political statement, or an attempt to become part of a social movement: he was simply a traditional man, who rejected the modern pace of life, atheistic consumerism, and the mind of the modern world.

As I sit in his chair writing this, I am reminded of the lesson he taught us by example: that good things, whether furniture or faith or the way one lives, are all inherited. They are not made, or bought, or thought up by clever folks in lecture halls or newsrooms or advertising agencies or even so-called "progressive" monasteries. They are our link with the inheritance of the past, the experience of the generations of holy people gone before us, who lived faithful lives in unseen places, never knowing about press releases, or websites, or stress leave, because the anonymous life needs none of this.

When as Orthodox Christians we consider how we must live, it is this inheritance, this example in the smallest things, that we try to emulate: the example of holy forefathers, not an adaptation of worldly "trends" in order to somehow make them resemble the Church.

This is the faith of the apostles. This is the faith of the fathers. This is the faith that has enlightened the universe.