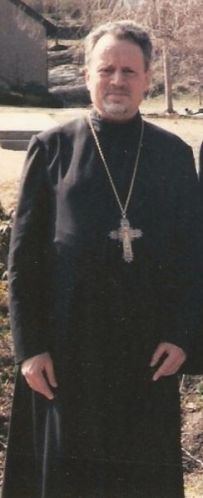

On the Sunday of St. Gregory Palamas we posted a sermon by Fr. Vsevolod Shpiller. While very well known and highly respected in Russia, particularly by those Muscovite faithful who lived through the final decades of the Soviet era, he is virtually unknown among anglophone Orthodox. Born in Kiev in 1902, he fought for two years in the White Army before emigrating first to Constantinople and then to Bulgaria, where he was ordained in 1934. In 1950 he returned to Russia, where he served for over thirty years atthe St. Nicholas Church in Kuznetskaya, Moscow. Despite enduring persecution and intrigue, he was able to gather a vibrant community of faithful, including many young members of the intelligentsia – a rarity at the time. Among his parishioners and spiritual children were a number of young men who went on to become well-known clergymen. Tape recordings of his sermons were widely (and secretly) circulated among the faithful. Fr. Vsevolod reposed on January 8, 1984. The following is a talk given by Fr. John Meyendorff in his honor in Moscow in 1992

My encounters with Fr. Vsevolod were very few in number. As I recall, one of them lasted perhaps five minutes, when he, as a member of a delegation from the Moscow Patriarchate, was in America and came to visit our St. Vladimir’s Seminary. As always, there was an official reception, at which everyone spoke about the usual insignificant and obvious topics. It was possible for no more than a few minutes, by meeting eye-to-eye and exchanging a couple of words, to establish a completely different kind of communication, on a different level, and not on the official bureaucratic-diplomatic level on which all the other meetings had taken place.Later there were several more encounters, when I was able to travel to Moscow and visit him in his apartment. I spoke with him about everything – both about the ecclesiastical situation and about the spiritual life – and here I simply cannot recall another instance when I ever felt differently. We even argued about certain things – about certain commonplace things – but all in one and the same tone.

It is possible that it was not only the spiritual life and ecclesiastical convictions that played a role in our closeness, but also spiritual immediacy and simple cultural commonality. Fr. Vsevolod belonged to the White Russian emigration, into which my parents were also born and to which they belonged; I understood these people. And, of course, in this regard Fr. Vsevolod presented a certain contrast to ordinary Soviet people. I do not like to speak like this, but there is no doubt that these seventy years have left a certain mark on people, just as a different mark has been left on us emigrants. This is not necessarily to say that one is better and the other is worse, mind you. But the cultural commonality with Fr. Vsevolod was perfectly obvious and he even made a special point of emphasizing it: “See, you and I understand each other so well because we belong to the same historical community.”

The most important of my own personal impressions was that Fr. Vsevolod saw in each person with whom he was speaking, first and foremost, a good that was established by God and that was positive. This was what he began with. This does not mean that he was blind or that he had the naïve blindness towards evil that is present in all of us – he did not have this blindness, of course. But this was the foundation, one that can be equated with love, because if the Lord Himself did not begin by first of all seeing in each one of us the image of God and His creation, He would have ceased engaging with His creation, if it can be put that way. Of course, this is not a theological affirmation – this could never happen – but nonetheless the Lord is love, and love loves the sinner, too, because the sinner is fundamentally God’s creation.

This, of course, concerns not only Fr. Vsevolod, but also the priesthood in general, as well as the Church and its life; it concerns our entire perception, our norms of perceiving reality and of people – a perception that, I think, must be in the Church. There is a naïve, rose-colored optimism, and then there is the actual spiritual certainty that one can only begin to communicate with another person, as well as to continue communicating, on the basis of this love and of the faith that there is something positive in the other person. This is in fundamental contrast to what can be called sectarianism. Sectarianism involves a certain self-assuredness in the group to which “I” belong and a certain truly demonic joy that everyone else is going to hell, and that the more people that go to hell the better; and the fewer people among whom “I” belong who go to Paradise, of course, also the better. This is in fact the opposite of what the Lord desires and of what is God’s will for all of creation and especially for the Church.

Fr. Vsevolod began his priestly service in the emigration during a period of ecclesiastical separation, although this separation was not total, since Vladyka Seraphim [Sobolev] was the administrator of the Russian parishes in Bulgaria. Fr. Vsevolod belonged to the Bulgarian Orthodox Church, by which he was nourished, but there was a separation with the Russian Church at that time. Nonetheless, after the Second World War both he and the same Vladyka Seraphim had the spiritual wisdom to find that very grain of truth in the Moscow Patriarchate, in the Russian Church. I assure you that this was not easy for them, and even now it is not always easy. Nevertheless, this is what ecclesiastical unity is.

The Church is not made up only of those who, like Fr. Paul Troitsky and Fr. Vsevolod Shpiller, are on a certain personal spiritual level and who understand each other in the Lord. All the saints ¬– both saints with a capital letter, and those with a small letter – understood each other in this way; there is a certain spiritual communion among those who live in God. But the Church is not made up of, and should not be made up of, only such people; it is called to save sinners, for the Lord came to save them, and not the righteous.

I think that in the history within which we are all called to live, with the entirely unique watersheds that make it up, this spiritual unity and ability to distinguish the true will of God is the most important – and indeed Divine – gift. I think the fact that Fr. Vsevolod possessed this gift is obvious both to all of you and to me, who am now standing among you in Russia and already looking at Fr. Vsevolod not just as an individual person, but also as a pastor who can be judged by his fruits. I think that the fruits he bore demonstrate that he was one of the luminaries of our church life in this century, this tragic and complex century in which so much evil has triumphed. But alongside this evil the Lord has sent such people as Fr. Vsevolod. That is everything I can say.

Translated from Russian.