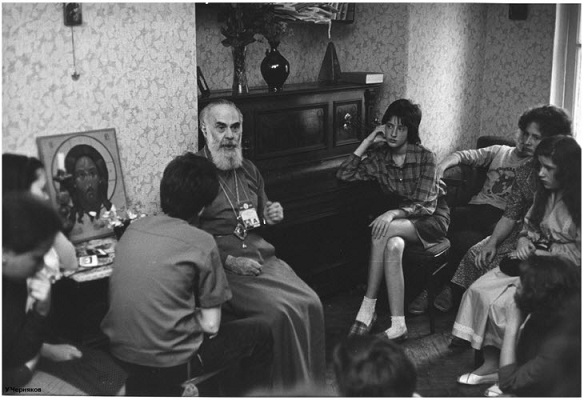

Metropolitan Anthony of Sourozh (+2003) granted the following interview – which was printed in Literator, an organ of the Leningrad Writers’ Organization, on September 21, 1990 – to M. B. Meilakh in London. Spoken on the eve of the collapse of the Soviet Union, Vladyka Anthony’s words have only gained relevance with time.

Vladyka, perhaps the events taking place in the Russian Church in the homeland are better seen from a distance?

You know, something might be seen more clearly from a distance, but something else is completely invisible, because the Russian reality is so complex, and made up of so many different currents, that one can pick up on one thing, but overlook a great deal else. It seems to me that the Russian Church has survived thanks to the Russian people’s love for the divine services and for liturgical beauty, about which Nilus of Sora spoke. I am not talking about the specifics of the Jesus Prayer now, but about that communion between the living soul and the Living God that takes place within the divine services, and that does not even necessarily depend upon understanding them, but simply upon standing before the Living God and upon the Living God being among us.

What is lacking in the Russian Church, of course, is the education of ordinary believers in questions of faith. Already in the nineteenth century, Leskov wrote that Rus’ had once been baptized, but had never been enlightened. And, indeed, a Russian knows God viscerally, in his soul. As Leskov says somewhere, he has “Christ in his bosom.” But, on the other hand, he still needs to acquire a great deal of knowledge – nothing specialized, simply a deep understanding of the meaning, for instance, of the Symbol of Faith and the Lord’s Prayer. The result, it seems to me, is that in Russia there are very many people who would not be able to defend their faith were it attacked, or be able to defend it in debate, but who would die for it, because they know with their entire being, viscerally, that what they believe in is truth, verity, and life.

Therefore, today the Church faces the question of how to educate believers, of how to teach them faith. First of all, this means the Gospel, which for several decades was unattainable as a book. This book somehow needs to be distributed among the people in such a way that more people would read it and would begin to live by that living power, fire, and life-giving power of our faith, by the words and image of Christ the Savior Himself. On the other hand, it is essential that people understand the divine services in which they take part. Not because some kind of intellectual understanding of the services is necessary, but because the divine services are constructed in such a way as to transmit the essence and content of our faith; the more one understands the divine services, the deeper one can delve into the content of Orthodoxy. Therefore, we face two issues today, which we will likely have more and more opportunities to resolve. The first is the education of the laity: in small groups, public meetings, and catechetical courses. The other task, which today is likewise gaining significance, is the training of young clergy. Today there are four new courses for preparing clergy (not yet seminaries) and this is very important. Here, of course, we should add the proviso that theological education alone does not make one capable of becoming a priest.

Being a priest is an art. There are things that theological schools do not teach, because they are wholly focused on theological education. I have met many young priests who have been insufficiently prepared in many areas and who have not yet fully entered parish life. For example, they do not know how to say confession, how to teach others to say confession, how to confess others, or what sources to use in preparing sermons. Spiritual writers and spiritual fathers spoke about different topics, but a sermon is spoken from the heart – you speak it to yourself, in a way. If it has not struck you in the heart, it will never strike anyone in the heart. If it does not flow from your mind and experiences, then it will not be conveyed to others, either. Next comes a question I have already touched upon: how to learn to pray not only with words, not only in accordance with the rules, but profoundly, and how to lead others into the mystery of this kind of prayer.

Finally, there is yet another problem. Many people – bishops, priests, and laity – came to me after the Council and said something like: “Look, we were raised under a totalitarian, authoritarian state. We have gotten used to doing what we are told – not to mention that many wait to be told even what to think – and now a new task lies before us. We need to learn how to make decisions and choices, but we do not know how to do this.” One very well educated and refined man asked me just that: “Tell me, how is this done?” I replied: “If I were to tell you how it is done, then you would still be doing it under control. You yourself need to learn how to think and act according to your conscience, to put yourself at risk (I do not mean on a mundane level), to take the risk upon yourself, of making a mistake. And then to think over what you have gotten right and what you have gotten wrong.”

That, of course, is the most important thing. But then another, related question comes up. It is obvious enough that the Church has been oppressed for many years, although it is unclear whether this period has really ended. But, at the very least, during perestroika, the Church is acquiring a somewhat different status. But does this new status not harbor new dangers of a similar kind? Is this new freedom, however limited, fraught with the danger of further unfavorable developments in terms of the Church’s cooperation with the state?

Political conformism has been a disease of the Russian Church for a long time. Even before the revolution, Church and state constituted, as it were, a single entity – moreover, one that was not always good for the Church. After the revolution the Church fell silent. During the period of oppression and extreme persecution, no one was able to speak out on political matters. And in order to learn how to think politically and to speak politically from within the Church, a long – or, rather, a profound – schooling is needed.

The Church cannot belong to any party, but at the same time it is neither non-partisan nor post-partisan. It should be the voice of conscience, one enlightened by the Divine light. In the ideal state, the Church should be able to say to any party or political current: this is worthy of man and God, and this is unworthy of man and God. Of course, this could be done from two positions: from a position of power and from a position of supreme powerlessness. It seems to me, and I am deeply convinced of this, that the Church should never speak from a position of power. It should not be one power among others operating in one state or another; it should be, if you will, just as powerless as God, Who does not use force; Who only beckons us, opening up the beauty and truth of things without imposing them; Who is like our conscience, telling us the truth while leaving us free either to listen to truth and beauty or to reject them. It seems to me that the Church should be precisely like that; if the Church should gain the position of a powerful organization, one with the ability to coerce or direct events, then there will always be the risk that it will want to wield power; but as soon as the Church begins to wield power, it will lose its deepest essence: the love of God and an understanding of those whom it is called to save, not to destroy and remake.

Finally, Vladyka, this is an extremely general question, but inasmuch as we know from your books and sermons that you look very deeply at what is going on in life and in the world, tell us how you asses the situation of Christians in the contemporary world with regards to everything that is happening now?

This is a difficult question, because what I would like to say will probably offend many people. It seems to me that the entire Christian world, including the Orthodox world, is now terribly estranged from the simplicity, integrity, and triumphant beauty of the Gospel. Christ and His group of disciples created a Church that was so deep, so wide, and so integral that it contained the entire universe within itself. Over the centuries we have turned the Church into one human society among others. We are fewer than the world in which we live and, when we talk about converting this world to Christianity, we are essentially talking about making everyone, to whatever degree possible, members of this limited society. This, it seems to me, is our sin.

We should understand that the Christian Church and its faithful should be faithful not only in terms of their worldview, but in terms of their lives and inner experiences; that our role consists of bringing light into this world, which is so dark and sometimes so frightening. The Prophet Isaiah, in one of the chapters of his book, writes: Comfort ye, comfort ye My people [40:1]. These words of God were addressed both to him and, of course, to us. “Comfort ye” means to understand what grief the whole world is in: materially, by its disarray, and spiritually, by its godlessness. This means bringing comfort, God’s kindness, God’s love, and God’s succor, which should envelop the entirety of the human person, into this world. There is no point talking to someone about the spiritual when he is hungry: let us feed him. It is no wonder that someone is mistaken in his worldview, since we have failed to share with him the living experience of the Living God. This, then, is our position in the contemporary world: we are the defendants. The world, in its rejection of God and the Church, says to us: “You Christians have nothing to give us that we need. You do not give us God; you just give us a worldview, which is quite dubious if it does not have a living experience of God at its heart. You give us instructions about how to live that are just as arbitrary as those given to us by others.” We need to become Christians – Christians in the image of Christ and His disciples. Only then will the Church acquire not power – that is, the freedom to use force – but rather authority, that is, the freedom to speak words that will make every soul tremble upon hearing them, opening up eternal depths in every soul. That, it seems to me, is our position and status today.

Perhaps I am pessimistic about our situation; but, after all, we are not Christians. We confess the faith of Christ, but we have turned it all into symbols. Our Passion services always hurt my soul. Instead of the cross on which a living young Man is dying, we have a beautiful service that can be moving, but that stands between this crude, awful tragedy and us. We have replaced the cross with an icon of the cross; the crucifixion with an image; and the story about the horror that took place with a poetic, musical reworking. This, of course, touches people: one can easily take pleasure in this horror, even experiencing it deeply, growing astonished, and then calming down. However, seeing a living person being killed is something completely different. That stays in the soul like a wound; after seeing it you will never forget about it; you will never again be the same. And this frightens me. In some sense, the beauty and depth of our divine services should be opened up and breached, so that every believer could be lead through this breach to the terrible and sublime mystery of what is taking place.

Yes, that is a very deep thought. After all, the contemporary world is regulated and arranged in such a way that, in principle, it can exist without God and without spirituality. It flows along in its tired manner, allowing one to sleep successfully through one’s whole life and then die.

But what strikes me as more frightening is that one can call oneself a Christian, and spend one’s whole life studying the depths of theology, and never encounter God. One can partake of the beauty of the divine services as a member of the choir or a participant in the services, but never break through to the reality of things. That is what is frightening. The unbeliever still has the chance to start believing; but for the pseudo-believer this opportunity is quite dim, since he already has everything. He can explain every detail of the divine services, of the Symbol of Faith, and of dogmatics – but then it suddenly turns out that he has never encountered God. And he is comfortable.

In Leskov, again, there is a passage in which it is said about someone: “Just imagine! He’s read all the way up to Christ!” And his interlocutor says: “Well, in that case, there’s no hope in changing him.” If only you could “read up to Christ” through the divine services, through the Gospel, through everything that we have, and not remain on this side… I became a believer through the Gospel and through a living encounter with Christ. Everything else came later, and everything else for me remains either transparent – not obscuring from me what I once experienced – or else I react to it with sharp pain. How, for example, during the Passion services can one easily sing certain things that are tragic? How is it possible, for instance, that during the consecration of the Holy Gifts we listen to the music of “We praise Thee,” but do not allow ourselves to be borne away by this singing into those terrible divine depths where the consecration of the bread and wine into the Body and Blood of Christ is taking place? I am not a musical person: I simply cannot understand how it is possible to sing during these moments; it seems to me that everyone should freeze in contemplative terror. And when the words “And make this bread” are heard, I do not even want to repeat the words of consecration. But this, of course, is my reaction; I do not want to say that it is correct, because I know people who are one thousand times more spiritually conscious and gifted than I am who are not concerned about any of this; who, to the contrary, are borne to those very depths. But I also know many people for whom all this [singing and words] is the whole point.

It takes enormous experience of prayer during the divine services for the services to stop existing in and of themselves and to become simply unnoticeable, just as fish do not notice the water in which they swim. I remember an old deacon in Paris, Fr. Evfimy, with whom I once sang and read on kliros. He read so quickly that I could not catch a single word. After the service – I was then nineteen, impudent and self-assured – I said: “Fr. Evfimy, today you robbed me of the whole service. And what’s worse, you yourself could not have experienced it, reading and singing the way you did!” He then burst into tears, saying to me: “Forgive me, I wasn’t thinking about you. But I was born in a terribly poor family in a pauper’s village. When I was seven they gave me to a monastery. Now, for sixty years already, I have been hearing and singing these words. You know, when I see a word, and even before I pronounce it, it’s like some kind of hand is pulling a string in me and my entire soul begins to sing!” Then I understood that his soul had become a sort of instrument and that the very smallest touch of these words – like the Aeolian harp, which would sing with a touch of the breeze – would make him respond, so that they did not even pass through his mind, heart, or consciousness. These words were already a song, already a religious experience. But, in order to get there, you have to become like that Elder, Fr. Evfimy, whom people laughed at because he had lost his voice and drank too much, and who did not stand out in any way – but his entire soul sang before God. May God grant this to everyone!

So, if anything I have said will be of use to anyone – wonderful!

Translated from the Russian