Sourse: Wonder

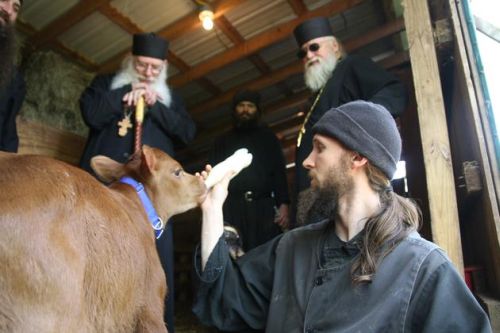

I have many fond memories from my monastic “youth,” as it were — my three years as a novice before tonsure at St. John’s Monastery now in Manton, California. It was a time of learning, a time of great growing pains, a time of being formed in the womb of the monastery to be born a new man in monastic life. It was a carefree time in many respects, too: not being one of the tonsured fathers, I never had to worry about where to get money to pay for everything, or the spiritual state of the monastery as a whole. Yet like all novices in all monasteries and in every age of our Church, I had plenty of tasks to keep me from being idle. These were my obediences, as we say in monastic parlance. And one of my main tasks near the end of my novitiate could have come right out of the early communities of Egypt or Palestine: being a goatherd.

Those who know me well would describe me as being intellectual, and adept at the workings of the mind. But as we know from Holy Tradition, the mind is not “where it’s at” for Orthodox Christians. The mind is important, yes, but it must be located in the heart — united to it. In this context it can rule with reason over the body to the glory of God. My abbot knew this about me, and as a good spiritual physician, “prescribed” to me the medicine of physical labour: hard work with my hands to bring me some balance. This labour of my hands was to watch over a small flock of dairy goats that the brotherhood had acquired. I was responsible, with another brother, for feeding the goats, milking them twice daily, pasturing them and processing the milk for the brotherhood’s needs.

At first, “balance” was the last word I would have connected with this obedience. I thought of myself as a morning person, and prided myself in being at Matins at 6 a.m. with bright eyes, unlike some of my brothers. The same was not the case for me anymore. Waking at 4 a.m. in order to do the barnyard chores left me dozing in Matins, and thanking God for curing me of that instance of haughtiness.

Watching and caring for our goats—who all had lovely Biblical names: Rahab, Judith, Tabitha and Hagar—was often hard work. Lifting and distributing hay bales; running after goats in the early weeks when they would escape the pen, but before they knew my voice; trying to hold the does in the stanchion for milking in the utter pre-dawn darkness. All around me was the chaos of a farm, with my ignorance thrown into the mix, and yet God beckoned me to prayer and trust in His providence, His control, His order present in the mess of my life, the straw-bestrewn pigsty (well, goat-sty) of my obedience. After a few weeks of faithfulness, the goats were used to me, and milking was a snatch. I still remember the peacefulness and silence, especially of winter mornings: fresh snow on the ground, a kaleidoscope of stars quietly blazing above the firmament, the goats happily eating oats, as I received their gift of milk for me and my brothers in prayer and thanksgiving. What an awesome thing to become so aware of one’s daily bread, or milk, in this way. I knew exactly what the goats had eaten and where, who had milked them, and how the cheese or yogurt had been made.

Herding the goats opened me up to a much greater understanding of the stewardship of the world that we as humans made in God’s image (including the image of royal authority) are charged with. I remember once thinking that my brother was to milk the goats the next morning, so I happily indulged in extra sleep before Matins. But in the normally reverent silence of the Six Psalms, I could hear the does bleating painfully – they had not been milked after all, and were starting to feel pain from their swollen udders. With haste I sought a blessing to leave the service and tend to them, and the episode impressed upon me how dependent they were on us to take care of them—and consequently, how utterly dependent we are on God for care. We “bleat” in the barnyard of our lives, needing food and nourishment, needing protection from the spiritual wolves and mountain lions seeking to devour us. God blessed me that year with a chance to learn from His shepherdly example in a quite literal way.

The monastic traditions in our church are filled with stories of elders and eldresses, simple monks and nuns who lived tied to the land precisely out of this love for nature and responsibility for tending it. I remember reading of many saints who had what appear to be “extraordinary” relationships with animals, showing such profound unity: St Gerasimos of the Jordan and his lion, St Melangell of Wales and her hares and St Seraphim of Sarov and his bear. In the later Western tradition, one instantly thinks of St Francis of Assisi and his birds. Mankind is called to reign over creation as stewards, but this does not mean “lording it” over animals and plants, crushing rock merely for ore, drowning oceans in oil in our lust for fuel. Rather, it means leading all things to unity, to communion, with each other and together with God, the Creator and Sustainer of all. My time as a goatherd still shines for me as an icon of that unifying vocation we all share in the Church, a gift given to all in our common royal priesthood. If we can do this, each in his or her own way, imagine what greater blessings God might shower upon us and His entire creation? At the very least, I can vouch for some good goat cheese that might come your way.