Source: http://www.monachos.net/library/Forgiveness_Sunday#_note-0

It is, at last, time for Great Lent to begin. The weeks of preparation are at their end; the gradual reduction and proscription of foods and activities comes now under the full weight of the Fast. The Church, on this very night of the ‘Sunday of Forgiveness’, has had its fabrics of whites and golds solemnly removed and replaced with deep purple: her customary garments of joy are exchanged for the attire of penitence. And so, kneeling and prostrate, her people look ahead to Pascha, the great feast of the Light, for the first time from within the context of the full Lenten discipline.

It is, at last, time for Great Lent to begin. The weeks of preparation are at their end; the gradual reduction and proscription of foods and activities comes now under the full weight of the Fast. The Church, on this very night of the ‘Sunday of Forgiveness’, has had its fabrics of whites and golds solemnly removed and replaced with deep purple: her customary garments of joy are exchanged for the attire of penitence. And so, kneeling and prostrate, her people look ahead to Pascha, the great feast of the Light, for the first time from within the context of the full Lenten discipline.

Thy grace has shown forth, O Lord, it has shone forth and given light to our souls. Behold, now is the accepted time; behold, now is the season of repentance. Let us cast off the works of darkness and put on the armour of light, that having sailed across the great sea of the Fast, we may reach the third-day Resurrection of our Lord Jesus Christ, the Saviour of our souls.[1]

The Sunday of Forgiveness stands, as others have written, at the ‘threshold of Great Lent’. The Vespers of this evening is a cardinal moment for many: a service in darkness by which their whole mode and attitude of being are propelled as if by a great wave into the ‘sea of the Fast’. There have been, already, four weeks of preparation for this moment; but this Sunday is the actual doorway into Lent, the threshold on the other side of which stands the fullest measure of ascesis that the Church metes out to the whole of her faithful throughout the world.

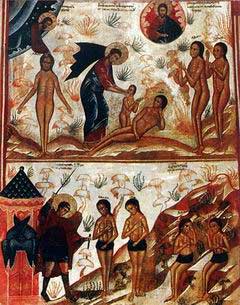

And with what voice do these faithful enter into the season of the Fast? We have already called this day the ‘Sunday of Forgiveness’, and by such a name is it most often known. But this title is an abbreviation, an emphasis on only one aspect of the day’s commemoration. There is another theme, too, and one which is in fact given far more space in the hymnography of the day: the expulsion of Adam from Paradise. As we stand at the threshold of the fast, we sing of him who stood before the gates of Eden. As we make ready to enter in to this season of preparation, we commemorate him who was cast out of primal Paradise. This is a Sunday of forgiveness, but it is also a Sunday of expulsion.

Adam sat before Paradise and, lamenting his nakedness, he wept: ‘Woe is me! By evil deceit was I persuaded and led astray, and now I am an exile from glory. Woe is me! In my simplicity I was stripped naked, and now I am in want. O Paradise, no more shall I take pleasure in thy joy; no more shall I look upon the Lord my God and Maker, for I shall return to the earth whence I was taken. O merciful and compassionate Lord, to Thee I cry aloud: I am fallen! Have mercy on me!’[1]

The scene painted by the hymns of the day is one of a great and terrible sorrow. Adam sits before the closed gates of Edenгin the sheer horror of his affliction, he cannot even standгand there, weeping, he laments the loss of so great a gift. Though already expelled from the Garden and chastised by the Word of God, it is at this moment that he truly realises the weight of his deeds and the seriousness of his state of affairs. ‘I am an exile from glory. I am in want. No more do I look upon the Lord my God and Maker’. As Great Lent begins, we are reminded in language stronger and more direct than any that has come in the preceding weeks of preparation, of the gravity of our condition in Adam.

Adam was cast out of Paradise through eating from the tree. Seated before the gates he wept, lamenting with a pitiful voice and saying: ‘Woe is me, what have I suffered in my misery! I transgressed one commandment of the Master, and now I am deprived of every blessing. O most holy Paradise, planted for my sake and shut because of Eve, pray to Him that made thee and fashioned me, that once more I may take pleasure in thy flowers.’ Then the Saviour said to him: ‘I desire not the loss of the creature which I fashioned, but that he should be saved and come to knowledge of the truth; and when he comes to me I will not cast him out.’[1]

Two things ought to strike us from within this particular hymn: first, the depth of the lament of Adam, with his acknowledgement of creation’s formation ‘for my sake’ and its loss because ‘I transgressed’; and second, the response made by the Saviour. There is no belittling of the Paradise from which Adam has been castгno attempt to ‘play down’ the glory of his previous home in order to accommodate the guilt felt at its loss. This was the cradle of ‘every blessing’ into which the loving Father had set His precious child, where even the flowers gave cause to rejoice. This, and nothing less, was the gift thrown aside in the transgression of the will of God. But we are struck, too, by the words uttered by the Saviour in response to the cries of Adam’s pitiful voice: ‘I desire not the loss of the creature which I fashioned, but that he should be saved and come to knowledge of the truth; and when he comes to me I will not cast him out.’

‘I will not cast him out.’ God’s words in this, the moment of primordial chastisement, are already the words of salvation. They are words of calling, of beckoning, of reconciliation. But they are also words of directive: ‘when he comes to me….’ God does not take fallen Adam and, with a divine fiat that would mean little to the long-term well being of humankind, magically place him back in the Garden whose gates Adam himself had locked shut. He knows that it is Adam’s heart that most desperately needs to be healed, needs to be turned away from the desire for its own ends and back to a desire for the heart of God Himself. And so the Saviour whispers to the weeping Adam, ‘When you come back to me, I will not cast you out’.

Then, in the consistent tradition of the Triodion, the words of the text make clear that the Saviour’s injunctions are not to the historical Adam alone, but to each of us as members of the one race of which he stands at the head.

Come, my wretched soul, and weep today over thine acts, remembering how once thou wast stripped naked in Eden and cast out from delight and unending joy.[1]

The preparatory weeks that have passedгthe Publican and the Pharisee, the Prodigal Son, the Last Judgementгhave gradually been preparing us to move the narrative of sin, fall, repentance and judgement into the first person; and today, whether we are ready for it or not, the sacred history of Adam and our own, personal histories as individuals are brought wholly together into one, communal story.

The Lord my Creator took me as dust from the earth and formed me into a living creature, breathing into me the breath of life and giving me a soul. He honoured me, setting me as ruler upon earth over all things visible, and making me a companion of the angels. But Satan the deceiver, using the serpent as his instrument, enticed me by good; he parted me from the glory of God and gave me over to the earth and to the lowest depths of death. But, Master, in compassion, call me back again.[1]

This is no longer a third-person narrative. No longer can I, standing outside and beyond the closed Royal Doors of the Church, feign innocence in the face of a story of ‘long ago and far away’. Lent is beginning, and as the personal tone of the hymns professes, this is to be my Fast, my exile, my return. Shall today be, too, the day of my expulsion?

Adam was cast out from the delight of Paradise: bitter was his eating, when in uncontrolled desire he broke the commandment of the Master and he was condemned to work the earth from which he had himself been taken, and to eat his bread in toil and sweat. Therefore let us love abstinence, that we may not weep as he did outside Paradise, but may enter through the gate.[1]

Amidst all the sombre reflections upon judgement and eviction, there is a quiet hope that abounds in the hymnography of this day. I stand beside Adam, I am joined to Adam, I cannot of myself escape from Adam’s condition. But through the Church, I need not suffer alone the whole torment of Adam. ‘Let us love abstinence, that we may not weep as he did outside Paradise, but may enter through the gate.’ The ‘sea of the Fast’ is not simply an ocean into which we are tossed and through which we must struggle to survive: Great Lent is also a harbour, a safe port wherein we may suffer our repentance in the surety of divine grace and tender compassion. Thus do we petition the Lord:

O God of all, Lord of mercy, look down compassionately upon my lowliness and do not send me far away from Eden; but may I perceive the glory from which I have fallen, and hasten with lamentations to regain what I have lost.[1]

It is in this context that the hymnography for this, the eve of Great Lent, takes its full meaning. We are called to see Adam’s life, to see our life, and to know the two as one. And then we are called to amend and to change our ways of living, thinking and acting (this being the true meaning of metanoia, repentance) from within the full scope of our lives in Christ. Through the story of our sin, our fall, our loss, we are thrust into a forum for change, wherein our greatest aid is the incarnate and resurrected Son of God Himself.

The arena of the virtues has been opened. Let all who wish to struggle for the prize now enter, girding themselves for the noble contest of the Fast; for those that strive lawfully are justly crowned. Taking up the armour of the Cross, let us make war against the enemy. Let us have as our invisible rampart the Faith, prayer as our breastplate, and as our helmet almsgiving; and as our sword let us use fasting that cuts away all evil from our heart. If we do this, we shall receive the true crown from Christ the King of all at the Day of Judgement.[1]

‘Let us use fasting that cuts away all evil from our heart.’ The entrance into Great Lent is made as the entrance into the full fray of the spiritual and physical battle we must each wage on the journey into the Kingdom of God. And though this is a battle we must each wage ourselves, we do not enter into it alone. As an invisible rampart, we have the Faithгthe truth of God revealed in His Son and in all the economy of space and time, borne alive in our hearts through the illumination of baptism. And as a visible rampart we have the Church, though here, too, there is the reality of the invisible. It is within the community of all the faithful, past and present, that we struggle towards resurrection, towards Pascha. It is amidst our neighbours that we stand in this arena and wage this battle. ‘If we do this, we shall receive the true crown’. From the usual context of ‘I’ and ‘thou’ in which we communicate day by day, Great Lent calls us to stand before the gates of Paradise in solidarity as the great family of humankind, the united children on the one God.

And so, forgiveness. Before we cross that threshold and step out into the ‘arena of the virtues’, we are reminded that no solidarity can ever truly coexist in the same framework as hatred, anger and resentment. A house divided against itself will not long stand. We are called, at this the doorway of the Fast, to do what Christ commands us always to do: to forgive one another in all love before presenting our offering at His temple. Too often do we ignore this command.

Often when I offer praise to God, I am found to be committing sin; for while I sing the hymns with my tongue, in my soul I ponder evil thoughts. But through repentance, Christ my God, set right my tongue and soul, and have mercy upon me.[1]

The first step in our journey through Lent must be this act of mutual forgiveness, of reconciling ourselves to one another in the context of the holy community in which we shall grow and advance together. If we set out upon the season of inner repentance without beginning here, in an act of fraternal repentance, then we will certainly find ourselves ‘committing sin while singing hymns with our tongues’. The gate of Paradise will only be more firmly shut.

But if this moment of mutual forgiveness is embraced and made real in our lives, then we shall be readily equipped both as individuals and as a community to fight worthily the battle before us. It shall not be we alone in the arena, but we the united Church who stand together in the contest that leads to all the brightness of the third-day Resurrection. And from within this community we will be able to find in our own selves the authentic voice of our genuine individuality, and shall be able to join the hymnist’s words to our own:

When I think of my works, deserving every punishment, I despair of myself, O Lord. For see, I have despised Thy precious commandments and wasted my life as the Prodigal. Therefore I entreat Thee: cleanse me in the waters of repentance, and through prayer and fasting make me shine with light, for Thou alone art merciful. Abhor me not, O Benefactor of all, supreme in love.[1]

Text by M.C. Steenberg, 2003