Leroy Bolier, an outstanding French expert on Russia, made a

very true observation, that “Russians are one of the few people who love what

makes up the very essence of Christianity: the Cross. Russians have not

forgotten how to value suffering, they perceive its power, feel the

effectiveness of redemption and know the taste of its bitter sweetness.”

Foolishness-for-Christ (yurodstvo) is none other than one of the forms, one of

the manifestations of this love for the Cross, as noted by Leroy Bolier. At the

very core of this podvig* (one of the greatest within human powers) is a feeling

of terrible guilt before God within the soul, which prevents it from taking

advantage of all the earthly comforts and impels it to suffer and be crucified

with Christ.

The essence of this exploit is in a voluntary acceptance of

The essence of this exploit is in a voluntary acceptance of

humiliation and insults in order to achieve the height of humility, meekness and

goodness of heart and by this to cultivate love even for one’s enemies and

persecutors. It is a life-and-death struggle not only with sin, but with the

root of sin – pride in all its secret displays. A fool-for-Christ (yurodivy) is

determined to follow the crucified Christ and to live keeping completely away

from all earthly comforts. But at the same time he is aware that such behaviour

threatens to create for him the reputation of a saint among the people and to

strengthen his self-love and increase his pride as being one of God’s elect –

which is one of the most dangerous rocks in one’s struggle for sanctity. So as

not to be taken for a saint, a fool-for-Christ rejects the outer aspect of

dignity and composure of mind that inspires respect and prefers to appear a

miserable, weak creature, deserving mockery and even violence. Deprivations to

which they subject themselves, their heroic, almost superhuman ascetic podvigs –

all this must seem to be devoid of any value and to evoke nothing but contempt.

In other words it is a complete denial of human dignity and even any spiritual

value of one’s own being – humility raised to a heroic degree and at times, as

it may seem on the surface, falling into the extreme. But in the heart of a

fool-for-Christ lives the memory of the Cross and the One Crucified, the slaps

on His face, the spitting and the flagellation, which encourages them at any

moment to endure any reviling and oppression for Christ’s sake.

* podvig = a spiritual exploit or feat that requires great

effort, sometimes one of even superhuman proportions.

Thus, for example, some fools-for Christ considered themselves

free from even the most elementary commitments to human society, from its

manners and morals, in order to challenge it. Not only did they present as

evidence of their denial their almost total nakedness and physical filthiness,

but even outward appearances of immorality (this happened even to those people,

whose sanctity was officially confirmed by canonization.).

A fool-for-Christ does not in the least seek esteem or love

from people; he even does not care to leave a good memory of himself among

people. This main principle was the source of the strength and courage shown by

fools-for-Christ, when they took their sorrowful way of exile and opposed evil

and injustice, regardless of their source or the respect or social position of

those who committed them. Professor Fedotov has provided a certain plan, which

helps us better understand the various aspects that make up this seemingly

paradoxical podvig:

1. The ascetic defiance of vanity, which is always dangerous

for monastic asceticism. In this sense foolishness-for-Christ is a feigned form

of madness and immorality for the purpose of being reviled by people.

2. Revealing the contradictions between profound Christian

truth and superficial common sense and moral law with the goal of exposing

oneself to the mockery of the world. (I Corinthians 1-4)

3. Serving the world through a peculiar kind of preaching,

delivered not in words or deeds, but through the power of the Spirit, and the

spiritual authority of the person, often invested with the gift of prophecy.

The gift of prophecy is ascribed to nearly all

fools-for-Christ. Spiritual enlightenment and a higher sense of reason become

the rewards for defying the human senses, just as the gift of healing is nearly

always connected with asceticism of the body and taking control over one’s own

flesh.

The first and the third aspects of foolishness-for-Christ are

podvig, service, and toil; they have spiritual and practical implications. The

second aspect provides the direct expression of religious needs. There is a

living contradiction between the first and the third aspects. Ascetic oppression

of one’s own pride is achieved at the cost of exposing other people to

temptation and the sin of condemnation, or even cruelty. Saint Andrew of

Tsaregrad besought God to forgive those whom he had provoked to persecute him.

Any act for the salvation of people evokes gratitude, respect, and thus

eliminates the ascetic purport of foolishness-for-Christ. That is why the life

of a fool-for-Christ is a constant swinging between acts of moral salvation of

people and acts of immoral scoffing at them. In Russia, foolishness-for-Christ

was dominated in the beginning by the first, or ascetic side; but by the 16th

century it was undoubtedly the third aspect – social service – that was

dominant.

It is customary to believe that the podvig of

foolishness-for-Christ is exclusively a calling of the Russian Church. This

opinion, however, contains an exaggeration of the truth. The Greek Church

venerates six fools-for-Christ. The Lives of two of them- St. Simeon (VI cent.)

and St. Andrew (IX cent.) were very extensive and interesting and were known in

Ancient Russia. Our ancestors especially loved the Life of St. Andrew for the

eschatological revelations that it contained. And the beloved Feast of the

Protection of the Mother of God made the “Saint from Tsaregrad” close to all

those in Holy Russia. Indeed, it was namely St. Andrew who, during Divine

Liturgy in Constantinople, had a vision of the Mother of God, covering the world

with her mantle – in honor of which the Feast of the Protection of the Mother of

God is celebrated on October 1st.

On the other hand, it should be pointed out that this variety

of ascetics came to Russia not directly from Byzantium, but quite unexpectedly,

in a roundabout way through the West and first penetrated in Novgorod. It is

interesting to note that the first saint fool-for-Christ in Russia, Prokopy

Ustyuzhsky (1302) – according to his Life composed in the 16th century, was of

German origin, “from the West, of the Latin tongue, and from the German lands”.

The podvig of foolishness-for-Christ was not known in Russian spiritual

experience until the 14th century. There had been only temporary, transient

forms of ascetics such as, for example, when St. Theodosius of the Kiev Caves

wore torn garments, or St. Isaac of the Kiev Caves pretended to be a fool in

front of his fellow-monks to evoke their mockery. Only from the 14th century did

foolishness-for-Christ become an original form of service to God, for the glory

of God, and society too. It reached its zenith in the 16th century.

Fools-for-Christ were considered at the time, in line with the saint princes, as

fighters for the triumph of Christ’s truth in public life. After the 16th

century there began a decline in foolishness-for-Christ, but it never entirely

vanished from the pages of the history of Russian spiritual experience. From the

18th century, the Church no longer recognized or blessed this unique form of

spiritual podvig.*

* In the 20th century the Russian Orthodox Church canonized

* In the 20th century the Russian Orthodox Church canonized

two fools-for-Christ: Blessed Xenia of St. Petersburg, and Blessed Alexis of

Yelnat. (Ed.)

It is important to note that the beginning of

foolishness-for-Christ correlated to the time when the sanctity of princes as

representatives of laymen began to decline. This is not an accidental

coincidence. New times required new forms of sanctity from laymen. The

fool-for-Christ became the successor of the saint princes in matters of serving

the people.

Even if foolishness-for-Christ was of western origin, on

Russian soil it acquired unprecedented development. It can be said without

exaggeration that this way of serving God tugged at the most profound

heartstrings of the Russian soul and perfectly fitted Russian people’s views on

religious life. Travelers from abroad, visiting Russia in the 16th century

reported on fools-for-Christ, describing them as “strange people wandering about

the streets with loose hair, a chain around their neck, with no clothes on

except linen rags around their waist.” And more: “These madmen honoured as

prophets could take from the shops whatever they wanted and the tradesmen poured

out their thanks to them without demanding any payment”. This enables us to

conclude that there were a lot of fools-for-Christ in Moscow of the 16th century

and they represented a special class of society. Noting that, Fedotov

continues:

“General respect for them with the exception, of course, of

some separate cases of mockery from children or mischief makers, the chains worn

for show, completely transformed the meaning of the old Christian

foolishness-for-Christ. Least of all it was an exploit of humility. At that time

foolishness-for-Christ was a form of prophetic service combined with an extreme

form of asceticism. And it was not the world that was outraging the blessed, but

the blessed were outraging the world.”

“The general decline of spiritual life from the second half of

the 16th century could not have bypassed foolishness-for-Christ. In the 17th

century there were fewer fools-for-Christ and they were not canonized by the

Church. Foolishness-for-Christ, like monastic sanctity, became localized in the

northern part of the country, returning to its Novgorod homeland. Vologda,

Totyma, Kargopol, Arkhangelsk, Vyatka – these were the towns of the last saint

fools-for-Christ. In Moscow the Church and state authorities started treating

fools-for-Christ with suspicion. They noticed among them the presence of pseudo

fools-for-Christ, really insane people or just frauds. A belittling took place

of Church feasts to already canonized saints (Blessed Basil). The Synod

completely stopped canonizing fools-for-Christ.

Having lost the support of the Church’s intelligentsia,

persecuted by the police, foolishness-for-Christ retreated among the common

people and underwent a process of degeneration. However, the common people

despite that obvious decline kept looking upon them as genuine representatives

of heroism pleasing to God. So “foolishness-for-Christ remained one of the most

characteristic phenomena of Russian folk religiousness; it was often outside the

Church, blending with sects hostile to the Church. Though in most cases it

remained faithful to the Church provided that the Church authorities did not

curb its activities or try to arrange its life and podvig in their own way,

disregarding any kind of social and Church discipline”. So an absolute

individualism constitutes one of the most distinguishing features of this

paradoxical spiritual trend.

As we saw, the first known fool-for-Christ in Russia was

Prokopiy, who had arrived from Germany and spoke in Latin. Whether he was German

or just came from the lands of the Holy Roman Empire is unknown. From Novgorod

he moved to Ustyg, pretending to be a fool and leading an unbelievably severe

way of life: he slept naked on church-porches, through the night he would pray

for the city and the people, receive food only from poor people, treat the rich

with contempt. He was abused, beaten, but in the end he won respect and after

his death he became profoundly venerated. A hundred years later the residents of

Ustyg decided even to build a chapel in his honour, but the clergy opposed it

and ordered the destruction of the work that had already been started. However,

local commemoration finally triumphed and was confirmed by the Moscow Council in

1547.

This first example was followed by others. Though during a long

period the breeding grounds of this new type of saints most probably remained

the northern Russian areas, which were in direct contact with the west and

particularly half-European, commercial Novgorod. It is not possible to

innumerate here all the fools-for-Christ, honoured by the Russian people, both

canonized and uncanonized. The number of those officially canonized as saints by

the Church is comparatively small: 36. The number of uncanonized

fools-for-Christ is quite large.

It would be interesting, however, to tell about one case of

this podvig, dating to a more recent time in the 18th century. This is Xenia,

who became very famous, especially in St Petersburg where her grave turned into

a place of popular pilgrimage. People pray to her along with the most

distinguished saints and a countless number of miracles are attributed to her

intercession.

Xenia was a married woman. Her husband’s name was Andrei

Petroff and he was a singer in a court choir. She was 26 when her husband, whom

she adored, died. Then she became a fool-for- Christ. Wicked tongues kept saying

that she simply lost her mind. She gave away her insignificant property,

including her dresses, but she left her husband’s clothes and started to wear

them, claiming that her name was not Xenia but Andrei. She started living in one

of the suburbs, but without having a permanent residence, moving from house to

house and disappearing at nights. She was often seen leaving the city and

praying in the field turning to all four corners of the earth. She was also seen

to work furtively at night bringing bricks for the construction of a large

church. Some time later, when her husband’s clothes turned into rags, Xenia

again started wearing women’s clothes, but in a very strange fashion. She wore

either a green or red skirt and a jacket and at the same time went barefoot or

wore torn shoes and no stockings. Gradually she stopped calling herself a man’s

name and became Xenia again. But never again would she submit to the conditions

of normal life, never restored her relationship with her relatives. She claimed

she did not need anything.

People of the neighborhood she lived in adored her. Mothers

gave her their babies to rock or to kiss – and this was considered a blessing.

Cabmen entreated her to sit down in their cabs just for a short time and after

that they were sure they would earn a lot during that day. Tradesmen tried to

thrust their goods into her hands, – if she touched them, the customers were

sure to come. Xenia became a great wonderworker in her lifetime. Her predictions

were on everybody’s lips. For example, on the day before Empress Elizabeth

Petrovna reposed (5 January 1761), Xenia was running along the streets of the

city shouting: “Make pancakes, tomorrow everybody in Russia is going to be

making pancakes!” (In Russia pancakes-bliny– are part of a funeral

repast).

After Xenia’s death her veneration continued to grow and

penetrated high society as well. Tsar Alexander III, while being heir to the

throne, fell ill with a recurring typhoid fever, and his wife, the future

Empress Maria Feodorovna, was very worried. Then one of the court servants

brought her a handful of earth from Xenia’s grave and advised her to put it

under the sick man’s pillow and to pray to the blessed one. The young grand

duchess followed the advice and her prayer was fulfilled. After the future

tsar’s recovery a daughter was born to them and she was called Xenia in honour

of this humble fool-for-Christ. And up till the revolution, among the

innumerable amount of believers who came to pray at the blessed one’s grave, one

would often see the Dowager Empress.

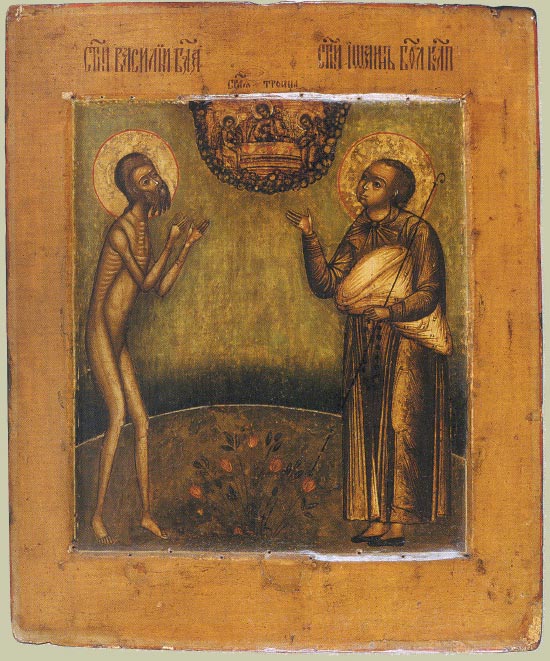

A type of fool-for-Christ was also reflected in Russian

literature. Pushkin in “Boris Godunov” depicted the blessed Ivan Big Cap, who

had lived in Moscow during the rule of Tsar Fyodor Ioanovich, Ivan the

Terrible’s son. People said about him that he liked ” to look at the sun and

meditate on the Sun of Truth”. Children would mock him, but he never punished

them, but would instead smile and foretell their future. Another fool-for-Christ

called Grisha is described in Leo Tolstoy’s book “Childhood. Boyhood. Youth”.

The pages describing the wanderer’s night prayers are fascinating and are not

inferior to the pages devoted to Starets Zosima in Dostoyevsky’s book ” The

Brothers Karamazov”.

After all that has been told above, it is probably possible to

conclude, that the fool-for-Christ is a type of saint that conveys better than

any other the spiritual features peculiar to Russian people. Love for Christ and

His Cross, love even unto death, and a willingness to imitate Him, are alive in

the heart of every Russian, consciously professing Christianity. In

fools-for-Christ this love is taken to an extreme. The means to achieve it are

through denial of this world and its wealth, exercised with the help of grace at

a supernatural level. Spiritual wandering and freedom amounting to anarchical

individualism develop to full extent in the life of a fool-for-Christ. Contempt

for any kind of form or reasonable limits, thirst for the absolute in

everything, abhorrence for any generally adopted rules, narrow-mindedness in any

form – all these things are fully expressed in foolishness-for-Christ. All these

things are flouted and mocked at by fools-for-Christ for the sake of Christ and

His Truth. Believing in transformation in the life to come, the fool-for-Christ

is sanctified by the Cross and infinite sufferings It brings. This is the

synthesis of the innermost aspirations of a Russian and the final clue to the

almost superhuman podvig of yurodstvo – foolishness for Christ’s sake.

http://www.russia-hc.ru/