There is a growing interest for the liturgical arts of the Orthodox Church outside of her. Many outside the Church have undertaken the task of not only painting icons, but ascribing to her theology as well. This interest has produced mixed results. Many people have joined the Church because of the icon. Others remain with the icon, pursuing this art, but staying outside the Church. In these circumstances it is better to let God work his wonders and guide the outcome, since he came into the world not to judge it but save it. We in the Church, therefore, have an obligation to exercise responsibility for her art and those producing it. For this reason, it is important to remember the Church’s theology the icon encompasses, as well the role of the iconographer. Through this short paper we hope to give some insight as to why icon painting for Orthodox liturgical use is preferred to be at the hands of not just any baptized Orthodox Christian, but by those with competent skill and practice. For this reason we have titled this paper Iconography and Creativity.

John Lickwar

Ouspensky recounts the Message really produces no new doctrine about the icon, instead, it instructs the iconographers in the norm and orientation of their creative activity. It speaks of the Church’s art being a fusion of dogmatic content, inner prayer and artistic creation (p.272 of Theology of the Icon). I believe this standard as true today, as it was when the Message first appeared, though it was originally thought to be commissioned by the iconographer Dionysius and used by him for instruction to his immediate apprentices and future ones. Authorship of the Message is between SS. Joseph of Volokolamsk and Nilus of Sora, with influence respectively from SS. Gregory Palamus, John of Damascus, Theodore the Studite, decisions of the 7th Ecumenical Council and utilizes the writings of St. Maximus the Greek, St. Macarius, monk Zenobius of Optina and others.

A starting point for us from the Message is the same power of the Holy Spirit, giving expression to the incarnate God man and giving iconographers their creative impetus. If iconographers are going to create icons to reveal the mystical life of the union between God and man, then it behooves them to be communicants of that same spiritual experience. This requires living within the mysteries of the Church, as her sacramental life is their life. The path of their personal salvation is deeply tied to their art; as much as anyone’s personal vocation can be living in the Church. This implies for the iconographer and any church artisan, active participation in the Church and communion with the Body of Christ. He must ascribe to the teachings of the Church and be taught by the Holy Spirit, for that same Holy Spirit enlivens the icon. It was never questioned that those involved in the making of icons would create their art outside the spiritual and sacramental experience of Christ’s Body, the Church. Clearly and simply their work is both the product and teaching of the Trinitarian life, the incarnation and inspiration of the Holy Spirit. Leonid Ouspensky summarizes this point of the Message to an Iconographer.

“The painter must be acutely aware of the responsibility that rests upon him when creating an icon. His work must be informed by the prototype it represents in order for its message to become a living active force, shaping man’s disposition, his view of the world and life. A true iconographer must commune with the prototype he represents, not merely because he belongs to the body of the Church, but also on account of his own experience of sanctification. He must be a creative painter who perceives and discloses another’s holiness through his own spiritual experience. It is upon this experience of communing with the archetype that the operative power of an iconographer’s work depends,” (pg. 270, Theology of the Icon).

The iconographer’s vocation is a liturgical one and innately linked to the icon. They are both grounded in the same truths and the iconographer cannot live and work detached from the content of the image. It is the venue of his creativity, because the painter cannot delineate the mere human body, apart from the divine nature enacted by grace. Outside of this spiritual experience, both icon and iconographer are void of their savor. Yes, such dry periods occur in the spiritual life of the Church’s iconographers, but the mysteries of the Church always provide the remedy of God’s grace to restore the person. The iconographer must participate in the spiritual dynamic of being a whole person. His skill is to utilize material elements, aspects and dimensions with obedience to grace in order to bring forth the whole icon. This is the same grace that constitutes his wholeness as a person. The icon is the delineation of a person’s lines, colors and shapes, made whole as represented symbolically in God’s uncreated light. Any other delineation presented as icon, but imitating the diminishing light in the perspective of realism, is a corruption of the icon. Such worldly, beautiful and sentimental images may suggest a connection with God and his will for man, but in reality reconfigures the icon into a historical record of the corrupt human and fallen world awaiting redemption. Such an image, in my opinion, is an iconoclasm and an iconographer who corrupts the icon in this way is an oxymoron. The subject of the icon must be the whole human person transformed by God’s divine Spirit to be light bearing. Between the icon and the iconographer God’s grace is at work in a mutual exchange, as the painter works on the icon, the icon simultaneously works on the painter. “We have beheld his glory, glory as of the only Son from the Father…And from his fullness have we received, grace upon grace.” (Gospel of John 1:14 &16) Standing in the Church before the ensemble of icons, we commune with the living God as through the eyes of our heart, as we would taste the heavenly bread and the cup of life at each Divine Liturgy. The words sung after having received the Eucharist are all encompassing also of our visual insight of the icon: “We have seen the true light! We have received the heavenly Spirit! We have found the true faith!”

This brings us to another point from the Message of vital importance, concerning beauty. Understanding that the iconographer participates in an artistic tradition, requiring more than aesthetic skill and technical knowledge makes one question, what more is expected of the iconographer and his art? The Message indicated there was per se no theory of art, as it may be understood today in the highly technical sense. Ouspensky strongly emphasized how the spiritual beauty of the icon corresponded directly to the authentic embrace of the Holy Spirit, not in theory but in creativity and spiritual life. Art sanctified was originally transcendent beauty expressed through shape, line and color. In his own words, he gleams the Message;

“The icon’s beauty was an expression of the holiness of its prototype. In other words the Orthodox doctrine of the deification of man was the theory of art. From this doctrine derives the practice of both spiritual life and art. Therein lays the organic unity of the spiritual and its artistic expression,” (p.272, Theology of the Icon).

Deification and beautification are one and the same. Their link with the doctrine of the indwelling of the Holy Spirit, allows this doctrine to be the theory of art for the icon. This theory is not merely a theoretical knowledge; it is an applied experience through spiritual insight. What characterizes the icon is the employment of line, form, color and materials, in a vision of the Divine world which has overcome the fallen one, transfigured and made present by the light of Christ through His Church. Ouspensky is not talking about the iconographer painting holiness, as this is impossible. Making an icon is a task utilizing lines, shapes and colors in a harmonious way that reverses light from diminishing to revealing the unity of the icon to its spiritual content. Thus the icon images a new beauty, a physical one which is purified as it becomes a referral to God’s uncreated light. Like the person, though in an obviously different way, the icon is physically prepared and transformed as bearer of God’s grace through light. The result is a revelation of beauty not of this world. It is what Dostoyevsky meant when he said, “beauty will save the world”. The overall concern of the Message is the decline of the liturgical art of the icon, confusing the beauty of artistic forms for spiritual depth, “the iconography of the period following that of Rublev witnessed the beginning of a progressive diminution of its spiritual meaning, of its deep structure. Beauty of artistic form began to take precedence over spiritual depth of the image, which decreased somewhat, causing dismay. The manner in which Message addressed its recipient is revealing: a call to vigilance is sounded,” (Theology of the Icon, p. 264).

The essence of God’s self revelation is to reveal us in divine beauty. The man saving work of the Holy Trinity does not merely restore us and the world back to our original image as it was prior to its corruption, rather our original image is brought from death to life in the new Adam. The incarnate God is constantly preparing us and the world’s material elements to reveal by his Grace, the image of that life to come. The icon visually delineates this eschatological dimension, the depth of which is projected into the viewer. In a presentation made at St. Vladimir’s Seminary this year, Metropolitan Hilarion (Alfeyev) describes the meaning of this dynamic in the making of icons.

“In a practical way, lines, forms, and materials are taken back to their simplicity, are brought into correspondence with the content of what is revealed, even an obedience to what is revealed, man’s participation in the life of God. Therefore the entire process of creating an icon is a humbling event,” (The full transcript is available from www.svots.edu).

Our last point, is to identify the way dogmatic content, inner prayer and artistic creation are woven together supporting the iconographer’s work. Ultimately these are enacted through the Mysteries of the Church. The Message does not insist that the techniques of prayer utilized by the hesychasts be demanded of every iconographer, for those techniques are not for everyone. But the Message does identify prayer and sacred stillness respectively as the inroad and state of being where a person’s relationship to God and their own sacred work as iconographers are enlightened. Both St. Andrew Rublev and Daniel the Black were monks, Theophan the Greek was not. The

“What is shown by the Russian icon is not so much the struggle against fallen nature as the victory over it, freedom recovered, when ‘the law of the Spirit creates the beauty of the body and soul which are no longer subject to the law of sin’ (Rom. 7:25; 8:2). The center of gravity does not lie in the hard struggle, but in the joy of its harvest, in the sweetness, the lightness of the burden of the Lord spoken of in the Gospel periscope read on the feast days of the holy ascetics: ‘Take my yoke on your shoulders, and learn from me, because I am gentle and humble in heart, and you will find rest for your soul, for my yoke is easy and my burden light’ (Mt 1:29-30). In the domain of art, the Russian icon is the highest expression of humility learned from God Himself. This is why the extraordinary depth of its content is associated with childlike joy, with intimacy and serenity,” (Ouspensky, Theology of the Icon, p.274).

I would like to reference a wonderful example from our own time of the integrity joining the iconographer to his work, by remembering the iconographer and iconologist Leonid Ouspensky. What is true of him is true with many other iconographers of the past who have left their influence in America. Archimandrite Kyprian Pyzhov, Pimen Sofronov, Father Gregory Krug, Nun Iuliania Sokolova, Photios Kontoglou and of the present who are too numerous to mention and the best well known. In the short book authored by Iconographer and Schemamonk Patrick Doolan entitled Recovering the Icon: The Life and Work of Leonid Ouspensky, Metropolitan Anthony (Bloom) of eternal memory, wrote a concise forward concerning Ouspensky. While Ouspensky’s contributions to the field of iconography are irreplaceable, his example offers something to be shared by new iconographers because he is part of a living tradition of iconography.

“Leonid Ouspensky was a man of not many words, but he had a presence which was sufficient for one to commune with him….

What impressed me in Ouspensky, was the quiet collectedness of all his person: he neither recoiled from you, nor moved into your inner space. Total, unaffected stillness is what I remember when I think of him. And you could read him, revealed in the icons he painted. For him, an icon was the projection in line and colors of an experience of things eternal; an experience that was personal: that of a person, a living member of the mysterious Body of Christ, not of a separate individual projecting, as it were, himself for others to see and admire. Through the person it was (as it should be) the experience of the whole Body, the Church, that reached one.

An icon was not to him an aesthetic creation, but a vision in lines and colors of the Divine world and it pervaded, conquered and transfigured the fallen world. It is only by looking deeply in the silence of contemplation, that one can enter into the spiritual world of Ouspensky, because it found expression in the terms of this world, both fallen and redeemed, both wrapped in twilight and at the same time pervaded by the Light of God.

If you want to know Ouspensky, stand in silence for a long while before an icon of his and receive the message that will allow you to commune with the contemplative silence out of which –within which- it was born, and the ardent faith which made him one who reveals to the world its true vocation and, indeed, its true nature.”

Never has the Church had to consider the possibility of icons being created by non-members and either gifted to the church or purchased by the church. Never has the Church had to respond to an increasing defense of the icon’s integrity and authenticity from outside her, while her theology of icons has historically developed from within her internal sacramental and liturgical life and prayer. The “Message to an Iconographer”, while in part a response to certain localized heresies, was produced at the height of hesychasm in Russia and the flowering of Russian art at the turn of the 15th century. The Orthodox Christian belief passed from Byzantium to Russia at a time when iconography, liturgy and hesychasm were at their height and under attack with the decline of the Byzantine Empire. Parallel this history, iconography, hesychasm and liturgy were taking their Russian shape. History’s lesson to us teaches that Orthodox iconography will not flourish in Tradition apart from the Church. It is interesting to note that at the present, in America, Finland, Russia and Greece, the revival of the iconographic tradition happens to coincide with a revival, in preparation and Eucharistic participation. This revival in certain segments of the Church coincides where prayers, not usually heard in the Divine Liturgy are now heard by the faithful. Where this has happened strategically and consistently throughout the Divine Liturgy, the mystical operation of God’s grace has not diminished and no dogma has been changed. What the faithful have always seen in the Orthodox icon they hear in literal true fullness. May our eyes be opened to see and ears opened to hear that in order for salvation and its Good News to remain the same, it is always sanctifying as it evolves in creativity, time and space.

Mr. John Lickwar is an Orthodox Christian and Iconographer. After completing his education at St. Vladimir’s Orthodox Theological Seminary, where he studied Liturgical Art under Archpriest Nicholas Ozolin. John continued technical training in iconography in Finland. He has produced icons for 30 years, and addressed churches, college and high school students concerning the meaning of Icon.

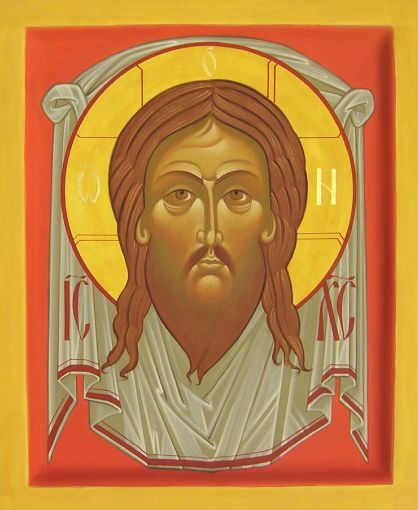

The icons presented above are painted by Mr. John Lickwar.