Source: Orchid Land Publications

Outsiders becoming aware of Orthodoxy–visiting a service, reading certain books of a “mystical” slant–decide that our religion is very “spiritual”–possibly too spiritual for their taste. Others visit a service and see us kissing icons; lighting candles; bowing or prostrating our bodies; venerating a Cross; the clergy wearing colorful vestments; Blessings of things with holy water or holy oil; blessing bread, grapes, and other objects on certain days; in fact, paying a lot of attention to what day it is; paying a great deal of attention to Christ’s fleshly generation in the all-holy Theotуkos, etc. . . . and conclude that Orthodoxy is awfully materialistic–too materialistic for their taste. What is it about Orthodox Christianity that lends itself to such contrary interpretations?

|

Chr. Yannaros (The freedom of morality), having observed that “the instinctive need for food . . . is transfigured in the context of the Church’s fasting,” he goes on in these terms: “The Christian does not fast in order to subjugate matter to the spirit . . . sone fasts because in this way one ceases to make the intake of food an autonomous act; one turns it into obedience to the common will and common practice of the Church and subjugates one’s individual preferences to the Church rules of fasting, which determine one’s choice of food. And obedience freely given always presupposes love: It is always an act of communion.” |

Before proceeding, we need to expose a frequent source of vagueness– spirituality–often a way to avoid the term religion, as when an unbeliever claims to cherish spiritual values. The term under scrutiny has so many slippery meanings and technical meanings as to make it mostly useless. Gnostics are spiritual because they reject material sacrament(al)s as aids to religion; they also refuse any revelatory value to time–tradition. Orthodox mystics are anything but spiritual in this sense, but only because they abandon the material comforts of the world in order to have more time for spiritual joy in constant doxologies sung to he all-holy Trinity. Spirituality can be used in a general sense of benignity, non-greedy or violent moral behavior, in a kind of thinking that rises above mundane concerns. The word is so hard to pin down in its most frequent uses that one is left not saying very much.

Another point calls for comment–the group of words: mysteric, mysterious, mystical. The first is equivalent to incarnational or Western sacramental, designating, as it does, the marriage of Grace (uncreated Energy for the Orthodox) with a material vehicle or instrument–water, bread, wine, oil, icon, etc.

Finally, we need to acknowledge that there are various kinds of middle ground between materialism (e.g. Marxism or some forms of magic) and Gnostic spirituality–which envisions no essential rôle for created matter in religion and no revelatory rôle for time in religion, postulating that matter and time get in the way of “spirituality.” One middle ground will be of concern here, one that does not view spirit and matter as being like oil and water: the mysteric outlook.

|

MYSTERIC |

GNOSTIC / NEO-PLATONIC |

|

Matter and body and time are vessels or vehicles of spirit. The vision of uncreated Light (Energy) is the ultimate goal.

|

Matter is incompatible with or hostile to spirituality. The emphasis is on preaching, hearing, reading words.

|

One will recognize Orthodoxy and Protestantism in the foregoing. In Orthodoxy, the “material” Incarnation (along with the human rôle of the Theotokos) and Resurrection are not overshadowed by the Crucifixion, however frequently and greatly the Cross is honored; see Rom. 4:25. Roman Catholicism accepts the marriage of matter and spiritual reality the way the Orthodox do, but the juridical overlay allows it to treat the physicomaterial Incarnation and Resurrection, however important, as being just as incidental to their juridicalized soteriology as Protestants do. Thus, magisterial Jesuit J. Pohle’s God, the Author of nature (1945, p. 151) says that “the Resurrection of Christ was not, strictly speaking, a chief or even contributing cause of our Redemption,” being an “integral, though not an essential, element of the Atonement.” (Quoted from G. Gabriel’s Mary the untrodden portal of God [Zephyr, 2000, p. 90].) The equally magisterial Latin theologian Dr. Ludwig Ott (Fundamentals of Catholic dogma, pp. 110-112) sees original guilt transmitted materially/physically “by natural generation”! So does the great Calvinist– Francis Turretin. On the other hand, the Latins do not go as far as Augustine and Calvinists in viewing sacraments as visible words.

|

In his Babylonian captivity of the Church, Luther claimed he could have the Mass anywhere at any time simply by having willed it. |

|

The notable Protestant writer, Louis Berkhof (Systematic theology, pp. 609-612), who treats a sacrament as a visible word or sermon–but there is a certain redundancy in that a sacrament has no efficacy in his view unless accompanied by a sermon. |

|

Both established forms of Western Christianity accept a virtual unity with the ontologically imparticipable uncreated Essence of God: With Aquinas, it is conceptual (“intentional”); with the Reformers, it is will-based and legal (“covenantal”). |

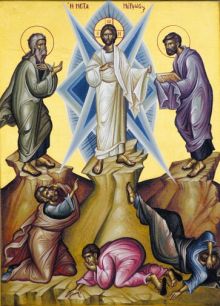

What is the long and short of all of this? Given the either-or logic that the human mind is prone to, a person with a “spiritual: outlook will view Orthodoxy as materialistic, while someone exposed to Orthodox “spirituality” and “mysticism” (along with mystericism) will focus on the enormously spiritual nature of Orthodoxy that so many non-Orthodox comment on. The miraculous spiritual vision of uncreated Light at Christ’s Transfiguration is ever present in Orthodox “spiritiuality” alongside of the materiospiritiual (mysteric, sacramental) Incarnation and Resurrection. The Crucifixion is an Offering up of Christ’s Immolation as the only perfect Worship till its time. It is not propititory (appeasing divine Wrath, though Greek is ambiguous) removes (expiates) the obstacles to incorporation into Christ–a worshiper’s ontologically becoming a new creating who ontologically shares Christ’s uncreated Life–the uncreated Energies of Grace. Christ offers Himself (in His ontological members) at each divine Liturgy; our prayers speak of Him as the Offerer and the Offered; the “separate” oblations or anaphoras are part of the One Offering. A Mystery is not an oil-and-water mix; it is the finite encasement of uncreated Energy in a material shell. The is foreign to the unmysteric outlook, which can only see one aspect (material or spiritual), not both aspects of our religion.