For “A Peace From Above”… “Teach Me Thy Justice”

Most Orthodox Christians, either as parishioners or as priests, have experienced the pain of waiting for members of the parish, a parish priest or a bishop to cease to behave in ways that are decidedly not Christian. Their behavior, their actions, strike us as failing to praise God as he deserves through humility, gentleness and mercy. The possibility that they have some good reason to behave differently helps us to be patient until such time as we better understand their motives. When, as sometimes is the case, we imagine that we have understood that their behavior is best explained by their weaknesses, the problem becomes more difficult. Shouldn’t we (as St. Paul suggests several times in writing about teachers of false doctrine) correct them fraternally by prayer and supplication, and later, if need be, exclude them from our midst? So far as common sense is concerned, we feel justified, but a nagging voice of conscience should by then tell us that maybe, as with our own families, we have ourselves wandered away from the higher road to peace, thus aggravating the difficulties others have in dealing with us.

Most Orthodox Christians, either as parishioners or as priests, have experienced the pain of waiting for members of the parish, a parish priest or a bishop to cease to behave in ways that are decidedly not Christian. Their behavior, their actions, strike us as failing to praise God as he deserves through humility, gentleness and mercy. The possibility that they have some good reason to behave differently helps us to be patient until such time as we better understand their motives. When, as sometimes is the case, we imagine that we have understood that their behavior is best explained by their weaknesses, the problem becomes more difficult. Shouldn’t we (as St. Paul suggests several times in writing about teachers of false doctrine) correct them fraternally by prayer and supplication, and later, if need be, exclude them from our midst? So far as common sense is concerned, we feel justified, but a nagging voice of conscience should by then tell us that maybe, as with our own families, we have ourselves wandered away from the higher road to peace, thus aggravating the difficulties others have in dealing with us.

We have many strategies by which we fail to bring a genuinely Christian perspective to the problem of anger and enmity within both parish and family life. The faith with which Christ supports all that is unsupportable leads finally to his impossible death on the cross. This cross-centered perspective is the horizon we need to make our own. Unless we do this, we will be deprived of our hope in Christian freedom and fall into a self-induced cynicism. Sooner or later we will conclude that the Beatitudes do not apply to our daily lives.

Until such time as our sense of self-vindicating outrage subsides, in reality it is I, not they, who is ceasing to be a Christian. This loss of sincerity, of openness to the destiny that God has offered us, occurs because of my refusal to be vulnerable to the other, even if the other seems to be persecuting me. In fact it is then that I am in great spiritual danger. In these moments we may not realize that our own Christian dignity in fact lies in just that experience which is described by the seventh and eight beatitudes as patient suffering:

Blessed are ye, when men shall revile you and persecute you and shall say all manner of evil against you falsely for my sake…fro so persecuted they the prophets which were before you.

Blessed are they which are persecuted for righteousness’ sake for theirs is the Kingdom of heaven.

The problem is that we don’t recognize that the thoughts that are passing through our minds and hearts in no way reflect the revelation of Christ to us in his Sermon on the Mount. The superiority of values in the Beatitudes as a personal, ascetic path to Christ is only clear to those who actually enter the path. St. Dionysios, a Syrian monk of the sixth century, gave us the term hierarchy (a sacred order), meaning a progressive adequation, an appropriate adaptation, of God’s grace to where we are on this ladder of ascent. If we bear our lot, we discover that the elevating effect of such a gracious hierarchy raises us to a higher level of vision and brings us into proximity with Christ. We are able to see the difficulties that hem us in as our very own cross. We begin to carry it out of free choice.

Thus the aspiration to patience gives a new meaning to the “evil” in others that otherwise I feel that I should bring to an end. I don’t say this moralistically. It has come to me after numerous mistakes and injustices committed by me in parishes in which I served, always because I had come to the point of feeling justified in saying “enough is enough.”

But what was I feeling? What had I had enough of? Enough of the other? Enough of being a Christian? Were they unworthy of my dedication? Why should I define their behavior by the limits of my comprehension? If a Christian way of life has any meaning, if it is in fact a witness of Christ’s passion, it is because my relations with the other are not defined by my needs. Do I want to live a genuine Christian life? If so it requires that I constantly seek to do unto others as I would have them do unto me.

Several times in my life my closest friends in the Church, persons toward whom I had great respect and with whom I shared an intimacy created by their qualities, since they lifted me to a higher plane of vision of my own life — these important friends have done things I would never have thought they were capable of. I was crushed. I grieved for months over what I thought was the destruction of our friendship, a brotherly bond which I felt had been made impossible by their misdeeds. I had needed them in order to be myself’. The person I was sure they were gave me a stronger faith. They had offered me a hand up to a purer plane of existence.

We read every Vespers in the Psalm 103 that the Lord makes of his servants “flames of fire.” I had previously found that flame in them, but now where was the flame of the Holy Spirit? Implicitly I retreated and turned my back on them and denied them. It was as if I was a better judge of their souls than God, in whom they had put their trust, who was clearly in a position to pardon those sinners in His own time? I let the confidence I had placed in them slip through my fingers and in so doing lost not only confidence in them, but also in God.

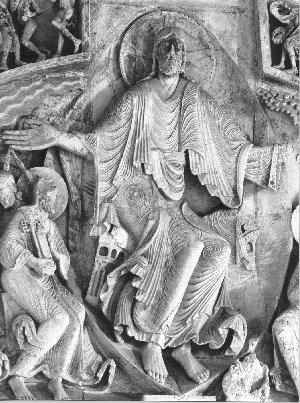

Suffering misfortune with patience is perhaps the highest expression of confidence in the Lord. This is not because it punishes and purifies us from our sins in a masochistic manner which concentrates on Christ’s human nature, but because it gives us the opportunity to participate in the same fortitude that Christ espoused in the constant and unrelenting adversity that he experienced. While being hounded from Galilee and Judea, Christ never wavers in proclaiming the good news of the coming of the kingdom of God in our midst. The horizon of his Father’s calling is never closer than when on his knees in the garden of Gethsemani, he is enveloped in anguish and prays to guard united the human and divine wills of his two natures in order to that the single person we have come to know as the Messiah, the anointed one. As St. Maximos the Confessor showed, after the fall, man’s “gnomic θέλημα” , (will as a deduced choice) no longer permits us to spontaneously chose that good which God offers us The human-divine person of Christ presents us with the model of the redemption of our fallen will; henceforth human will is free to commune fully with God’s will for us.

Suffering misfortune with patience is perhaps the highest expression of confidence in the Lord. This is not because it punishes and purifies us from our sins in a masochistic manner which concentrates on Christ’s human nature, but because it gives us the opportunity to participate in the same fortitude that Christ espoused in the constant and unrelenting adversity that he experienced. While being hounded from Galilee and Judea, Christ never wavers in proclaiming the good news of the coming of the kingdom of God in our midst. The horizon of his Father’s calling is never closer than when on his knees in the garden of Gethsemani, he is enveloped in anguish and prays to guard united the human and divine wills of his two natures in order to that the single person we have come to know as the Messiah, the anointed one. As St. Maximos the Confessor showed, after the fall, man’s “gnomic θέλημα” , (will as a deduced choice) no longer permits us to spontaneously chose that good which God offers us The human-divine person of Christ presents us with the model of the redemption of our fallen will; henceforth human will is free to commune fully with God’s will for us.

If complaining makes of us cowards, long-suffering makes us clear-headed about how a fallen world operates. Much of human communication takes place on the level of provocation, usually over inconsequential matters, but tiring to us. If this is so, it is because the other cannot yet see us as a dependable friend. By testing our patience, he/she is trying to see how long we are willing to put up with them. Are we ready to “share spaces with them” as Jessica Rose put it in a recent book. And what can we say inside ourselves while this is going on: Psalm 142:, which is prayed every morning at Matins, show us a path forward:

Deliver me, O Lord, from mine enemies:

I flee unto thee to hide me.

Teach me to do thy will,

for thou art my God: thy spirit is good;

lead me into the land of uprightness.

In the course of several decades I have served under five or six bishops, and I must admit that only one of them met my expectations — and finally even the failing of this exception was hard for me to accept. Why were “worthy bishops” so hard for me to find? I have of course obeyed them all, but I could have collaborated more fruitfully if I had been able to give them my confidence. Why was I withholding my confidence? I believe now that I had not realized that the confidence I failed to place in them would have emerged if I had gone ahead and collaborated whole-heartedly with these bishops rather than standing back and waiting until they proved their qualities to me. After all, they must have seen my own limitations, yet even so that did not prevent them from placing their trust in God when they ordained me deacon and later priest.

This was despite the fact that I had already learnt some basic lessons when seeking out a “good” confessor. Early on, when my own confessor was far away, I had adopted the habit of going to confession with the priest for whom I had the least esteem. This exercise in humility proved fruitful, for these men never failed to give me good advice and to sincerely pray for me. The need to respect a person, or to judge him as worthy of my admiration, had found a fitting limit since even I had to confess that such judgment of others was incompatible with asking for forgiveness from God.

All this is formulated in the final exhortation of the Apostle James’ epistle, if one cares to read it with a open, undefended heart:

Be patient, therefore, brethren, until the coming of the Lord. Behold, the farmer waits for the precious fruit of the earth, being patient over it until it receives the early and the late rain. You also be patient. Establish your hearts, for the coming of the Lord is at hand. Do not grumble, brethren, against one another, that you may not be judged; behold, the Judge is standing at the doors. As an example of suffering and patience, brethren, take the prophets who spoke in the name of the Lord. Behold, we call those happy who were steadfast. You have heard of the steadfastness of Job, and you have seen the purpose of the Lord, how the Lord is compassionate and merciful.

But above all, my brethren, do not swear, either by heaven or by earth or with any other oath, but let your yes be yes and your no be no, that you may not fall under condemnation. Is any one among you suffering? Let him pray. Is any cheerful? Let him sing praise. Is any among you sick? Let him call for the elders of the church, and let them pray over him, anointing him with oil in the name of the Lord; and the prayer of faith will save the sick man, and the Lord will raise him up; and if he has committed sins, he will be forgiven. Therefore confess your sins to one another, and pray for one another, that you may be healed. (James 5:7-20)

The Greek word μακροθυμίας, often translated rather weakly as “patience,” might better be rendered as “long-suffering.” This has to do with forging the future by waiting on the Lord. As we read in Proverbs: “Do not lose heart, because the Lord will be coming soon. Do not make complaints against one another, brothers, so as not to be brought to judgment yourselves… You have heard of the patience of Job, and understood the Lord’s purpose, realizing that the Lord is kind and compassionate.” (Proverbs 3:34 LXX)

The Apostle James exhorts us not swear by heaven or by earth, which I understand to mean not to finalize our judgments. Rather he proposes that we should sing psalms with the joyful, and pray for those in trouble. So like Elijah, who prayed for rain until it did rain, we our encouraged to pray with our faith for the sick man and the Lord will raise him up again (whatever that “up” may be), and he will be forgiven. Saving a soul from death due to his/her sins, says St. James, covers a multitude of sins, presumably including our own. So here is the “reason” not to judge: so that we will not be judged and so that our sins will be forgiven.

To sum up, we have been in a critical situation ever since we were old enough to blame others for our own limitations. The fact that others have their own limitations does not change anything. We are constantly in danger of being hemmed in by the way that we view others, by the ways we (and they) become disappointed and aggressive.

Daily life is for a Christian best compared with that of the Hebrews fleeing Pharaoh’s armies across the Red Sea. The only thing that can save them is their faith in the God of Abraham, Isaac and Jacob. Their ability to follow Moses across this sea and into the desert is what keeps the walls of water from drowning them. As long as they believe that the waters of that passage are more dangerous to them than Pharaoh’s charioteers, as long as they trust in their own fears more than the call of Moses to escape Egypt, they have no prospect of salvation.

Peter had the same experience as he attempted to walk towards Christ on the waters of the Sea of Galilee. The moment he turned his gaze away from Christ and looked at the waters, he began to sink. The security of our own expectation had been decried by Jesus:

It is the pagans of this world who set their hearts on these things. Your Father well knows you need them. No, set you’re your hearts on his kingdom, and these thing will be given you as well. There is not need to be afraid little flock, for it has pleased your Father to give you the Kingdom. (Luke 12:22)

Each time we put on the cross around our neck, it is recommended that we say the words of Christ: “If anyone wants to be a follower of mine, let him renounce himself and take up his cross every day and follow me. For any one who wants to save his life will lose it; but anyone who loses his life for my sake will save it.” (Luke 9:23)

This self-giving loss of life is the way to the deep self-knowledge that Christ has promised us: “Whosoever cometh to me, and heareth my sayings, and doeth them I will shew you to whom he is like: He like a man which built an house, and digged deep, and laid the foundation on a rock… (Luke 6:47)

The rock is God’s divine law. Not the civil law, that is often little more than a screen hiding our collective sins that are the ruin of society, what the French call a cache-misère, but a law that, for those who follow, makes us free and thankful to God for revealing his justice to us.

The whole of the psalm 118 (119) describes how the Christian “treasures your promises in my heart … be good to your servant and I shall live … exile though I am on earth … my soul is overcome with an incessant longing for your rulings … I am sleepless with grief, raise me up as your word has guaranteed … I run the way of your commandments since you have set me free…”

The long suffering patience of the psalmist derives its strength from waiting for the Lord to save him, an offer of loving intervention that gives him life. That life is God’s justice. God is just in all his works and does justice to his servant. We ask God to teach us his statutes. What does that mean exactly? The word justice or statutes in Greek (δικαίμα) means both acts of justice towards man, justification of his creature, and God’s judgment regarding our acts.

In this sense the whole set of contemporary political proposals of fundamental universal human rights glosses over the more fundamental fact that it is God who has rights over man. It is this that makes the Beatitudes a realistic program for daily life. It is possible to be long-suffering since the Lord of great goodness is long-suffering with us. Herein lies the peace from above we have been thirsting after! Here is the peace that the life-giving cross brings us… “because the kingdom of God means righteousness and peace and joy brought by the Holy Spirit.” (Romans 14:18)

____________________________________________________________

Fr. Stephen Headley, rector of the parish of St. Etienne the Proto-martyr and St. Herman of Auxerre (Moscow Patriarchate) in northern Burgundy, is a researcher in social anthropology in the French National Center of Scientific Research (CNRS, Paris)

Vézelay, France. Member of the editorial board of In Communion, Father Stephen after having published several books on religion in Indonesian, is currently involved in research on the “Transmission of the Orthodox Faith in contemporary Moscow”.