External Arrangement

Orthodox churches generally take one of several shapes that have a particular mystical significance. The most common shape is an oblong or rectangular shape, imitating the form of a ship. As a ship, under the guidance of a master helmsman conveys men through the stormy seas to a calm harbor, so the Church, guided by Christ, carries men unharmed across the stormy seas of sin and strife to the peaceful haven of the Kingdom of Heaven. Churches are also frequently built in the form of a Cross to proclaim that we are saved through faith in the Crucified Christ, for Whom Christians are prepared to suffer all things.

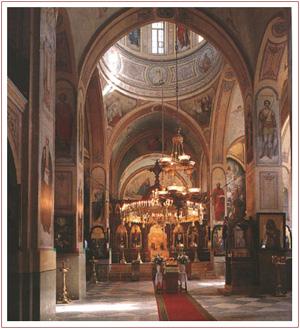

Internal Arrangement

The interior of an Orthodox church is divided into several parts. One enters the church through the Porch where, in ancient times, the keepers (Penitents forbidden to enter the church proper) stood. From the Porch one entered the Vestibule (Narthex; Lity – Greek; Pritvor – Russian), in ancient times a large, spacious place, wherein the Catechumens received instruction while preparing for Baptism, and also where Penitents excluded from Holy Communion stood. Here was found the Baptismal Font and it is here that the Church Typikon specifies that penitential services (such as Compline, Nocturns and the Hours) be served.

The Iconostasis

The most prominent feature of an Orthodox church is the Iconostasis, consisting of one or more rows of Icons and broken by a set of doors in the center (the Holy Doors) and a door at each side (the Deacon’s Doors), In ancient times, the Iconostasis was probably a screen placed at the extreme Eastern end of the church (a tradition still preserved by Russian Old-Believers), but quite early it was moved out from the wall as a sort of barrier between the Nave and the Altar, with the opening and closing of curtains making the Altar both visible and inaccessible.

The Altar and Its Furnishings

The Altar which lies beyond the Iconostasis, is set aside for those who perform the Divine services, and normally persons not consecrated to the service of the Church are not permitted to enter. Occupying the central place in the Altar is the Holy Table (Russian – Prestol), which represents the Throne of God, with the Lord Himself invisibly present there. It also represents the Tomb of Christ, since His Body (the Holy Gifts) is placed there. The Holy Table is square in shape and is covered by two coverings. The first, inner covering, is of white linen, representing the winding-sheet in which the Body of the Lord was wrapped. The outer cloth is made of rich and bright material, representing the glory of God’s Throne. Both cloths cover the Holy Table to the ground.

The Bells

A striking component of Orthodox worship is the ringing of bells. Every daily cycle of public divine services starts with the ringing of bells and no one who has witnessed the procession around the church at Holy Pascha can forget the almost continuous ringing of all the church bells. In Pre-Revolutionary Moscow, for example, travelers invariably commented on the stirring clamor of the more than 1600 bells of the city ringing simultaneously at the Pascha of Our Lord. Usually a separate structure, the Bell Tower, was constructed to contain the bells, but more often in modern times a belfry is erected over the entrance to the church building, within which the bells are placed.

Candles and Their Symbolism

Lit candles and Icon lamps (lampadas) have a special symbolic meaning in the Christian Church, and no Christian service can be held without them. In the Old Testament, when the first temple of God was built on earth – the Tabernacle – services were held in it with lamps as the Lord Himself had ordained (Ex. 40:5, 25). Following the example of the Old Testament Church, the lighting of candles and of lampadas was without fail included in the New Testament Church’s services.

External Arrangement

Orthodox churches generally take one of several shapes that have a particular mystical significance. The most common shape is an oblong or rectangular shape, imitating the form of a ship. As a ship, under the guidance of a master helmsman conveys men through the stormy seas to a calm harbor, so the Church, guided by Christ, carries men unharmed across the stormy seas of sin and strife to the peaceful haven of the Kingdom of Heaven. Churches are also frequently built in the form of a Cross to proclaim that we are saved through faith in the Crucified Christ, for Whom Christians are prepared to suffer all things. Less frequently churches are built in the shape of a circle, signifying that the Church of Christ shall exist for all eternity (the circle being one of the symbols of eternity) or in the shape of an octagon, signifying a star, for the Church, like a star, guides a man through the darkness of sin which encompasses him. Because of the difficulties of internal arrangement, however, the latter two shapes are not often used.

Almost always Orthodox churches are oriented East -West, with the main entrance of the building at the West end. This symbolizes the entrance of the worshipper from the darkness of sin (the West) into the light of Truth (the East). This rule is violated only if the building had been previously constructed for another purpose, or if services are conducted in a private home, for example, when the entrance and main portion have been arranged according to convenience. On the roof of Orthodox churches are usually found one or more cupolas (towers with rounded or pointed roofs), called crests or summits. One cupola signifies Christ, the sole head of the Christian community; three cupolas symbolize the Most-Holy Trinity; five cupolas represent Christ and the four Evangelists; seven cupolas symbolize the Seven Ecumenical Councils which formulated the basic dogmas of the Orthodox Church, as well as the general use in the Church of the sacred number “seven”; nine cupolas represent the traditional nine ranks of Angels; and thirteen cupolas signify Christ and the Twelve Apostles.

A peculiar feature of Russian Orthodox churches is the presence of onion-shaped domes on top of the cupolas. In the early history of the Russian Church, especially in Kiev, the first capital, the domes of the churches followed the typical Byzantine rounded style, but later, especially after the Mongol Period, Russian churches tended toward the onion domes, which, in many places, became quite stylized. Historians are not in agreement as to the origin of this particular style, but some point to the possible influence of Persia on this peculiar feature of Russian church architecture, while others argue that since this style was more popular in the far North of Russia, it had a practical application, in that the shape was particularly suited to shed the large amounts of snow common in the region. Every cupola, or where there is none, the roof, is crowned by a Cross, the instrument of our salvation. The Cross may take one of many different shapes, generally according to the national tradition of a particular local Church. In the Russian Church, the most common form is the so-called three-bar Cross, consisting of the usual crossbeam, a shorter crossbeam above that and another, slanted, crossbeam below. Symbolically, the three bars represent, from the tup, the signboard on which was written, in Hebrew, Latin and Greek, Jesus of Nazareth, the King of the Jews (John 19:19); the main crossbeam, to which the hands of Jesus were nailed; the lower portion, to which His precious feet were nailed. The three-bar representation existed in Christian art from very early times in Byzantium, although usually without the bottom bar slanted, which is particularly Russian. The origin of this slanted footboard is not known, but in the symbolism of the Russian Church, the most common explanation is that it is the pointing upward to Paradise for the Good Thief on Jesus’ right and downward to Hell for the Thief on His left (Luke 23). Sometimes the bottoms of the Crosses found on Russian churches will be adorned with a crescent. In 1486, Tsar Ivan IV (the Terrible) conquered the city of Kazan which had been under the rule of Moslem Tatars, and in remembrance of this, he decreed that from henceforth the Islamic crescent be placed at the bottom of the Crosses to signify the victory of the Cross (Christianity) over the Crescent (Islam).

Internal Arrangement

The interior of an Orthodox church is divided into several parts. One enters the church through the Porch where, in ancient times, the keepers (Penitents forbidden to enter the church proper) stood. From the Porch one entered the Vestibule (Narthex; Lity – Greek; Pritvor – Russian), in ancient times a large, spacious place, wherein the Catechumens received instruction while preparing for Baptism, and also where Penitents excluded from Holy Communion stood. Here was found the Baptismal Font and it is here that the Church Typikon specifies that penitential services (such as Compline, Nocturns and the Hours) be served. In modern times, except for certain monasteries, the Vestibule has fallen into disuse with the decline of the Catechumenate, and has virtually disappeared in church architecture.

The main body of the church is the Nave, separated from the Sanctuary (Altar) by an Icon screen with doors, called the Iconostasis (Icon stand). The walls of the Nave are usually decorated with Icons and frescoes or paintings, before many of which are hanging lit lamps (lampadas). On each side, near the front, are usually found portable Icons – called Banners – which are fastened to staffs. These are carried in triumphant processions in like manner to the ancient military banners of victory, which they imitate. Especially noticeable in traditional Orthodox churches is the absence of any seating (except perhaps for benches placed along the walls and at the rear). The Holy Fathers, deemed it disrespectful for anyone to sit during the Divine services (except at certain explicit moments of instruction or Psalm reading) and the open spaces were seen to be especially conducive to the many bows and prostrations typical of Orthodox worship

At the extreme Eastern end of the church is found the Altar (or Sanctuary), with two small rooms – the Sacristy and the Vestry – at either side, separated from the Nave by the Iconostasis. The Iconostasis is placed near the edge of the platform upon which stands the Altar and the part of the platform which projects out into the Nave is called the Soleas (an elevated place) where the Communicants stand to receive Holy Communion and where the Celebrants come out for public prayers, sermons, etc. At either side of the Soleas are places for two Choirs, called the Kleros (meaning lots, since in ancient times Readers and Singers were chosen by lots). At the front of the Soleas, before the Holy Doors, is an extension of the Soleas, called the Ambo (ascent) which is the specific spot where the faithful receive Communion and where sermons are given. In many Greek churches, there is a separate place to the side of the Soleas for the delivery of sermons-the Pulpit.

Sometimes placed in the center of the Nave is a raised platform called the Cathedra. Here the Bishop stands when he is vested and it is from here that parts of the services are performed by him. In some churches a special throne is set at the side of the Nave for the Bishop’s use.

The Iconostasis

The most prominent feature of an Orthodox church is the Iconostasis, consisting of one or more rows of Icons and broken by a set of doors in the center (the Holy Doors) and a door at each side (the Deacon’s Doors), In ancient times, the Iconostasis was probably a screen placed at the extreme Eastern end of the church (a tradition still preserved by Russian Old-Believers), but quite early it was moved out from the wall as a sort of barrier between the Nave and the Altar, with the opening and closing of curtains making the Altar both visible and inaccessible.

The Holy Fathers envisioned the church building as consisting of three mystical parts. According to Patriarch Germanus of Constantinople, a Confessor of Orthodoxy during the iconoclastic controversies (7th-8th Centuries), “the church is the earthly heaven where God, Who is above heaven, dwells and abides, and it is more glorious than the [Old Testament] tabernacle of witness. It is foreshadowed in the Patriarchs, is based on the Apostles…, it is foretold by the Prophets, adorned by the Hierarchs, sanctified by the Martyrs, and its high Altar stands firmly founded on their holy remains….” Thus, according to St. Simeon the New Theologian, “the [Vestibule] corresponds to earth, the [Nave] to heaven, and the holy [Altar] to what is above heaven” [Book on the House of Cod, Ch. 12]. Following these interpretations, the Iconostasis also has a symbolic meaning. It is seen as the boundary between two worlds: the Divine and the human, the permanent and the transitory. The Holy Icons denote that the Savior, His Mother and the Saints, whom they represent, abide both in Heaven and among men. Thus the Iconostasis both divides the Divine world from the human world, but also unites these same two worlds into one whole-a place where all separation is overcome and where reconciliation between God and man is achieved. Standing on the boundary between the Divine and the human, the Iconostasis reveals, by means of its Icons, the ways to this reconciliation.

A typical Iconostasis consists of one or more tiers (rows) of Icons. At the center of the first, or lowest, tier, are the Holy Doors, on which are placed Icons of the four Evangelists who announced to the world the Good News – the Gospel – of the Savior. At the center of the Holy Doors is an Icon of the Annunciation to the Most-Holy Theotokos, since this event was the prelude or beginning of our salvation. Over the Holy Doors is placed an Icon of the Last Supper since, in the Altar beyond, the Mystery of the Holy Eucharist is celebrated in remembrance of the Savior Who instituted the Sacrament at the Last Supper.

At either side of the Holy Doors are always placed an Icon of the Savior (to the right) and of the Most-Holy Theotokos (to the left). In addition, next to the Icon of the Savior is placed that of the church, i.e., an Icon of the Saint or Event in whose honor the church has been named and dedicated. Other Icons of particular local significance are also placed in this first row, for which reason the lower tier is often called the Local Icons. On either side of the Holy Doors, beyond the Icons of the Lord and His Mother, are two doors – Deacon’s Doors – upon which are depicted either sainted Deacons or Angels – who minister always at the heavenly Altar, just as do the earthly Deacons during the Divine services.

Ascending above the Local Icons are several more rows (or tiers) of Icons. The tier immediately above are those representing the principal Feasts of the Lord and the Theotokos. The next tier above that contains Icons of those Saints closest to the Savior, usually the Holy Apostles, Just above the Icon of the Last Supper is placed an Icon of the Savior in royal garments, flanked by His Mother and St. John the Baptist, called the Deisis (prayer), since the Theotokos and the Forerunner are turned to Him in supplication. As these Icons (Apostles, Theotokos, and Forerunner) are arranged in order on either side of the Savior the tier is usually called the Tchin (or rank). Often this tier was to he found just above the Local Icons and below the Feast Day Icons.

The next row usually contains thy Old Testament Saints – Prophets, Kings, etc. – in the midst of which is the Birthgiver of God with the Divine Infant Who is from everlasting and Who was their hope, their consolation, and the subject of their prophecies. If there are more tiers, Icons of the Martyrs and Holy Bishops would be placed above the Old Testament Saints. At the very top of the Iconostasis is placed the Holy Cross, upon which the Lord was crucified, effecting thereby our salvation.

As pointed out, the central place of the Iconostasis is occupied by the Holy Doors, because the Mystery of the Holy Eucharist celebrated within the Altar, is brought forth through them to the faithful. They are also called the Royal Gates (or Doors), since the King of Glory passes through them in the Holy Eucharist. Behind the doors is placed a curtain which is opened or closed, depending on the solemnity or penitential aspect of a particular moment of the Divine services.

The Altar and Its Furnishings

The Altar which lies beyond the Iconostasis, is set aside for those who perform the Divine services, and normally persons not consecrated to the service of the Church are not permitted to enter. Occupying the central place in the Altar is the Holy Table (Russian – Prestol), which represents the Throne of God, with the Lord Himself invisibly present there. It also represents the Tomb of Christ, since His Body (the Holy Gifts) is placed there. The Holy Table is square in shape and is covered by two coverings. The first, inner covering, is of white linen, representing the winding-sheet in which the Body of the Lord was wrapped. The outer cloth is made of rich and bright material, representing the glory of God’s Throne. Both cloths cover the Holy Table to the ground.

Antimension

In the first centuries of Christianity, the Divine Liturgy was celebrated on the tombs of the Martyrs and this was celebrated by the Bishop. Later, as the Church expanded and the size of a typical Diocese with it, the Bishops of the early Church began to ordain Priests as their representatives to the growing number of Christian communities. Only with the Bishop’s permission could a community and its Priest serve the Liturgy and the same holds true today. One of the vehicles by which these important ancient practices are effected today is a simple piece of cloth, folded within another, and resting always on the Holy Table of every Orthodox church – the Antimension. The Antimension is a rectangular piece of cloth, gold in color, measuring about 18 by 24 inches, and while on the Holy Table it is folded within another cloth, red in color, called the Iliton, which represents the swaddling clothes and the burial shroud of Jesus Christ. Depicted on the top of the Antimension is an Icon of the Burial of Christ, along with Icons of the four Evangelists, as well as Saints Basil the Great and John Chrysostom, for whom the usual Divine Liturgies are named. Sewn into every Antimension is an incorruptible relic of a Saint, making real the early liturgical connection with the Martyrs who died rather than renounce Christ, and whose blood, after the Blood of Christ, formed the very foundation of the Church.

Printed on every Antimension are the words: “By the grace of the All-Holy, Lifegiving Spirit, this Antimension, the Holy Table, is consecrated for the Offering on it of the Body and Blood of our Lord in the Divine Liturgy.” Each one is signed by the ruling Bishop of the Diocese and placed on the Holy Table, constituting his permission for the community to exist as an Orthodox parish and to celebrate the Liturgy. This is so, since true Christianity has always held that without the Bishop there is no Church and through the Bishop comes our unity of Faith and Communion which is Orthodoxy. The word Antimension is a combination of Greek and Latin which means in place of the table. While Holy Tables were always to have been consecrated and relics placed inside of them, it was not always possible for the Bishop to visit each community to do so. For that reason, Bishops consecrated cloths or boards and sent them to each community to be used in place of the consecrated Holy Table. This also allowed for portable Holy Tables for travelers. The use of the Antimension is mandatory, even on Holy Tables which have been consecrated, and a Priest is not permitted to celebrate the Divine Liturgy without it. Military Chaplains and Missionaries also use it instead of the table when serving in remote areas.

Also placed on the Holy Table are two indispensible items: the Cross and the Book of the Gospels, The Cross is placed there both as a sign of Christ’s victory over the Devil and of our deliverance. Since the Lamb of God was slain on the Cross for our salvation, it is especially appropriate that it be placed upon the Holy Table where the Bloodless Sacrifice is offered “on behalf of all and for all.” As it is the Word of God, the Book of the Holy Gospels is placed on the Holy Table, signifying that God is mystically present. It is usually richly-adorned and as it is the Book of Life, its Governing may not be of the skins of dead animals (i.e., leather), but is usually made of precious metals adorned with jewels. At the center of the cover is usually represented Christ, with the four Evangelists – Matthew, Mark, Luke and John – at the four corners. As the Holy Table represents the sepulchre of the Lord, upon it, at the rear, is placed the Ark (or Tabernacle), so-called because of its general shape, within which are placed the Holy Gifts {Reserved Sacrament) used for the Communion of the sick. Candlesticks are also placed on the Holy Table, signifying the Light of Christ which illumines the world.

In addition to the above, a natural (not artificial) Sponge is usually placed beside the Antimension with which to brush off the particles from the Paten into the Chalice. Also found is a vessel containing the Holy Chrism used for Chrismation, and also a Sick-Call Kit (the Ciborium) within which are to be found a small chest for the Holy Gifts, a small Chalice and Spoon, a small vessel for wine and a sponge to clean the Chalice with. In addition, a small chest, called the Artophorion is placed on the Holy Table during Great Lent, within which is placed the consecrated Lamb(s) used for the Presanctified Liturgy (if the same is not placed in the Tabernacle). Often a canopy is suspended over the Holy Table, representing the heavens over the earth, from which is suspended a dove with outstretched wings (the Fix), representing the Holy Spirit. (In many places, the pre-sanctified Lamb was placed in the Pix during Great Lent.)

Behind the Holy Table a seven-branched Candlestick is usually placed (seven being the sacred number), and sometimes a large Processional Cross. Behind this, at the extreme East end of the Altar is a raised place, called the High Place (or Bema), upon which is placed the Cathedra (Bishop’s Throne), with seats for the Priests on either side. During the Liturgy, the Priests (representing the Holy Apostles) sit at either side of the Bishop (representing the King of Glory). [In modern times, the Cathedra is usually found only in Cathedrals and large Monasteries.]

On either side of the Bishop’s Throne arc placed ceremonial Fans, with which, in ancient times, the Holy Gifts were fanned to keep away insects. Now they are carried in solemn processions, signifying the six-winged Seraphim who minister at the Divine services, and who are represented iconographically upon them. Above the High Place is an Icon of the Savior and on both sides Icons of the Holy Apostles or (more often) Holy Bishops. Before the Icon of the Savior is suspended a lampada, called the High Light.

The Bells

A striking component of Orthodox worship is the ringing of bells. Every daily cycle of public divine services starts with the ringing of bells and no one who has witnessed the procession around the church at Holy Pascha can forget the almost continuous ringing of all the church bells. In Pre-Revolutionary Moscow, for example, travelers invariably commented on the stirring clamor of the more than 1600 bells of the city ringing simultaneously at the Pascha of Our Lord. Usually a separate structure, the Bell Tower, was constructed to contain the bells, but more often in modern times a belfry is erected over the entrance to the church building, within which the bells are placed. The purpose of ringing the bells is to call the faithful to services, to inform those absent from divine services of the various important liturgical moments of the services, as well as calling the worshippers to concentrated attention at these same moments. It is also used to signal the arrival of the Archpastor at the church or monastery. There are four basic types of bell-ringing in the Russian Church: The Announcement (Blaguvest’ – announcing); the Peal (Trezvon – three bells); Chain-ringing (Perezvon – across (or linked) bells); and the Toll (Perebor – broken (or interrupted).

Candles and Their Symbolism

Lit candles and Icon lamps (lampadas) have a special symbolic meaning in the Christian Church, and no Christian service can be held without them. In the Old Testament, when the first temple of God was built on earth – the Tabernacle – services were held in it with lamps as the Lord Himself had ordained (Ex. 40:5, 25). Following the example of the Old Testament Church, the lighting of candles and of lampadas was without fail included in the New Testament Church’s services.

The Acts of the Apostles mentions the lighting of lamps during the services in the time of the Apostles. Thus, in Troas, where Christ’s followers used to gather on the first day of the week (Sunday) to break bread, that is, to celebrate the Eucharist, them were many lights in the upper chamber (Acts 20:8). This reference to the large number of lamps signifies that they were not used simply for lighting, but for their spiritual significance. The early Christian ritual of carrying a lamp into the evening service led to the present-day order of Vespers with its entry and the singing of the ancient hymn, “O Jesus Christ, the Joyful Light”, which expresses the Christian teaching of spiritual light that illumines man – of Christ the Source of the grace-bestowing light. The order of the morning service of Mating is also linked to the idea of the Uncreated Light of Christ, manifested in His Incarnation and Resurrection. The Fathers of the Church also witnessed to the spiritual significance of candles. In the 2nd Century, Tertullian wrote: “We never hold a service without candles, yet we use them not just to dispel night’s gloom – we also hold our services in daylight – but in order to represent by this Christ, the Uncreated Light, without Whom we would in broad daylight wander as if lost in darkness”. The Blessed Jerome wrote in the 4th Century that “In all the Eastern Churches, candles are lit even in the daytime when one is to read the Gospels, in truth not to dispel the darkness, but as a sign of joy…in order under that factual light to feel that Light of which we read in the Psalms (119:105): Thy word is a lamp to my feet, and a light to my path”.

St. Sophronius, Patriarch of Jerusalem, wrote in the 7th Century: “Lampadas and candles represent the Eternal Light, and also the light which shines from the righteous”. The Holy Fathers of the 7th Ecumenical Council decreed that in the Orthodox Church, the holy Icons and relics, the Cross of Christ, and the Holy gospel were to be honored by censing and the lighting of candles; and the Blessed Simeon of Thessalonica (15th Century) wrote that “candles are also lit before the Icons of the Saints, for the sake of their good deeds that shine in this world”.

Orthodox faithful light candles before the Icons as a sign of their faith and hope in God’s help that is always sent to all who turn to Him and His Saints with faith and prayers. The candle is also a symbol of our burning and grateful love for God. During the reading of the Twelve Passion Gospel at Holy Friday Matins, the faithful hold candles, re-living our Lord’s sufferings and burning with love fur Him. It is an ancient custom of Russian Orthodox Christians to take home a lit candle from this Service and to make the Sign of the Cross with it on their doors in remembrance of Our Lord’s sufferings and as protection against evil.

At Vespers on Holy Friday, when the Plashchanitsa (Epitaphion) is borne out of the Altar and also during the Lamentation Matins of Holy Saturday, the faithful stand holding lit candles as a sign of love for Christ Crucified and Dead, showing their faith in His radiant Resurrection. On Pascha itself, from the moment of the procession around the church, in memory of the Myrrhbearers who proceeded with burning lamps to the sepulchre of the Lord, the faithful hold lit candles in their hands until the end of the Paschal Service, expressing their great joy and spiritual triumph Since ancient times, at hierarchical services special candle-holders have been used. The faithful reverently bow their heads when blessed by the Bishop with the dikeri, representing the two natures of Christ – His Divinity and His humanity, and the trikeri, representing the Holy Trinity. Candles are also lit during the celebration of the Holy Eucharist.

Holy Baptism is celebrated with the Priest fully vested and all the candles lit. Three candles are lit before the baptismal font as a sign that the Baptism is accomplished in the Name of the Holy Trinity; and the person to be baptized (if an adult) and the sponsors hold lit candles in their hands during the procession around the font as an expression of joy at the entry of a new member into the Church of Christ, At the betrothal ceremony, the Priest hands the bride and bridegroom lit candles before they enter the church to receive the Sacrament of Matrimony, throughout which they hold the lit candles as a symbol of their profound love for each other and of their desire to live with the blessing of the Church. At the Sacrament of Holy Unction, seven candles are lit around the vessel of Holy Oil as a sign of the grace-bestowing action of the Gifts of the Holy Spirit. And when the body of a deceased person is brought in the church, four candles are placed about the coffin to form a cross to show that the deceased was a Christian. During the Funeral service, as well as Memorial services, the faithful stand with lit candles as a sign that the deceased’s soul has left this world and entered the Kingdom of Heaven – the Unwaning Light of God. During the Vespers portion of the Liturgy of the Presanctified Gifts, the Priest blesses the congregation with a lit candle and censer, proclaiming, “The Light of Christ illumines all!” On the Eve of the Nativity of Christ and the Theophany, a lit candle is placed before the festal Icon in the middle of the church to remind us of the birth and appearance on earth of Christ Our Savior, the Giver of Light. At all Divine Liturgies, lit candles are carried in procession at various parts of the service.

Thus candles and lampadas are lit at all Church services, all with a wide variety of spiritual and symbolic meanings; for it is God Who said, “Let light shine out of darkness,” [and] Who has shone in our hearts to give the light of the knowledge of the glory of God in the face of Christ (1 Cor. 4:6). So too, lit candles in the church are also an expression of the worshippers’ adoration and love for God, their sacrifices to Him, and at the same lime of their joy and of the spiritual triumph of the Church. The candles, by their burning, remind one of the Unwaning Light which in the Kingdom of Heaven makes glad the souls of the righteous who have pleased God.

Source: http://www.orthodoxworld.ru/english/hram/index.htm