July 29, 2013

As politicians debate the fate of Syria’s Christian minority, reportedly targeted by Muslim fundamentalists for supporting Bashar Al Assad’s regime, the country’s Christian sites seem to have been forgotten in the two-plus-year civil war.

“They cut off the head of the statue of Mary (Lady of the Two Worlds) in Syria’s Jisr El Shaghour region,” wrote Rev. Georges Massouh, a Lebanese Greek Orthodox priest, adding that it was still more acceptable than slaughtering human beings.

If the attack aimed to terrorize Christians, they will remain in Syria, whose every grain of soil is a witness to its Christianity, and will be martyrs of love, peace, and Christ’s eternal presence in them, he said this week in the daily Annahar.

Earlier this year, Tarek Al Abed wrote in Assafir, another Lebanese newspaper, that Christians and Muslims had coexisted in the Qalamoun region, noted for its Christian villages.

But the ongoing conflict has definitely taken a toll on Christians, their sites, and the language of Christ.

The Bible may have been translated into every language, but the tongue in which Jesus Christ would have preached is almost extinct, spoken by a few thousand people in Syria, mostly in the village of Maaloula.

Nobody can read or write Aramaic since there’s no alphabet and no visual record of it, I was told on a visit in 1991. Today it would be hard to quantify how many speakers remain, or how many have survived the fighting.

Linguistic scholars have disputed that contention, arguing that several hundred thousand people converse daily in Aramaic.

They agree that the “Western” dialect spoken in Syria, Lebanon and Palestine before the Muslim conquest, and thought to be the language Jesus used in spreading the gospel, is fast disappearing.

However, the “Eastern” dialect, the scholars argue, lives on – albeit in limited form – in Iraq, Iran, southeastern Turkey, and a sliver of some former Soviet republics.

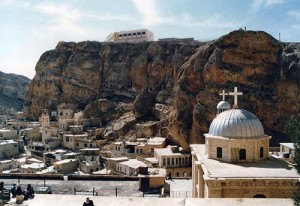

One of the Semitic languages, spoken Aramaic of the “Western” variety is limited to the residents of Maaloula, a village 50 kilometers (31 miles) north of the Syrian capital Damascus.

It is also the popular language of people in the nearby villages of Jaba’deen and Najafa, although it has to compete with Arabic, the official language of Syria, as well as the closely linked Syriac and Hebrew.

Whatever records existed about the language were burned during the French colonial period, explained a Greek Orthodox nun at the St. Takla monastery in the craggy mountain village overlooking acres of once-rich agricultural land.

St. Takla’s monastery, one of the oldest in Christendom, dates back to the First Century A.D., and its founder was a disciple of St. Paul the apostle.

She was reportedly born to heathen parents in Iconia on the Greek-Turkish border and was persecuted for her beliefs by her ruler father.

Locals said St. Takla was fleeing her pagan father and his soldiers when she reached Maaloula. Its high mountains blocked her passage and it seemed she would be killed.

She is then said to have raised her hands in passionate prayer, which was answered when the mountain split, allowing her an escape route to safety.

St. Takla built a monastery, which contains her remains, on the spot from where she took flight.

For centuries it stood as a refuge for countless visitors and believers, convinced the water that oozes slowly from the rocky ceiling near the saint’s tomb had mysterious and curative qualities.

The word Maaloula originates from “Om Al Maalouleen” (mother of the afflicted), in reference to St. Takla’s healing powers, I was told, but evolved to signify passage or entryway.

The walls of the saint’s crypt are lined with valuable gifts donated by visitors who prayed to the young woman and had their prayers answered.

Situated between the steep rocky hills of the Qalamoun Mountains, Maaloula was most noted for its annual feast of the cross, when residents lit bonfires along various hilltops to mark the occasion and dance to the steady beat of drums.

I wonder if they still do, or dare to.

The village, a UNESCO World Heritage Site, is surrounded by caverns, once used by the early Christians, to hide from invading Roman legions, and the entire region was thought to be rich with treasures.

Villagers believed they were sitting on several layers of different civilizations, but little was done to promote the village’s historic and religious attractions for many years.

The once rich surrounding agricultural lands were also hit by several years of drought, leaving only patches of green on an otherwise dry mountain.

Many of Maaloula’s residents either migrated to the capital or ventured further afield to the United States and Brazil in the 1920s in search of greener pastures.

When I visited, the farmers produced enough of the village’s own consumption of wheat, tomatoes, apricots and peaches, but one member of each family invariably commuted to Damascus to supplement their income.

Another major Christian site in Syria is Our Lady of Saydnaya, a magnificent edifice on a hill overlooking the village by the same name.

It boasted a library of hundreds of valuable manuscripts housed in the 547 A.D. structure.

The convent is a Greek Orthodox establishment directly dependent on the Patriarchate of Antioch, with its seat in Damascus, and which owns several properties in Syria and Lebanon.

Legend has it that Emperor Justinian I of Byzantium, while crossing Syria with his troops en route to battle with the Persians, stopped in the Syrian desert to rest and search for water.

In the distance he spotted a gazelle, which he hunted with great energy until he was overcome with fatigue on a rocky hill.

The gazelle was headed to a spring of sweet water when it was suddenly transfigured into an icon of the Holy Virgin and shone with a bright light.

Stretching from the icon, according to the story, a hand reached out to the emperor, saying: “No, thou shalt not kill me, Justinian…but thou shall build for me a church, here on this hill.”

Among the sacred sanctuaries of the Greek Orthodox faith, the Saydnaya convent is second only to Jerusalem as a holy visiting place of pilgrimage in the Middle East.

Source: Horizon Weekly