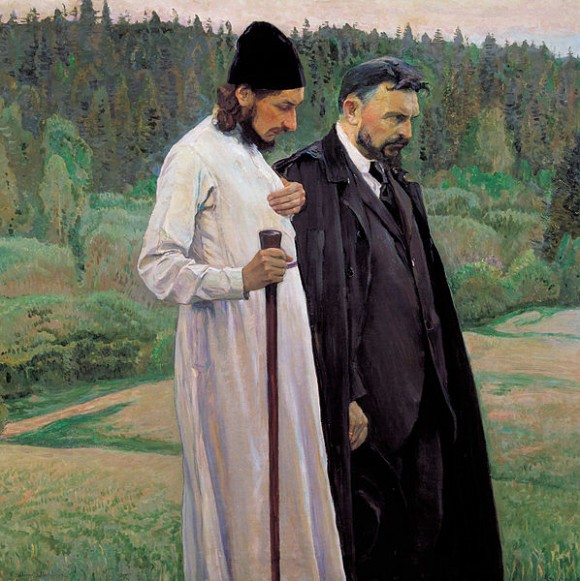

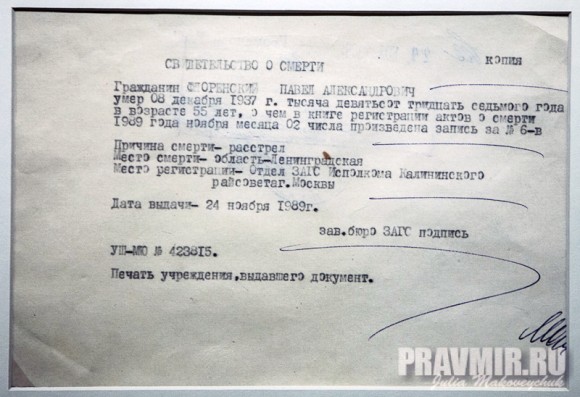

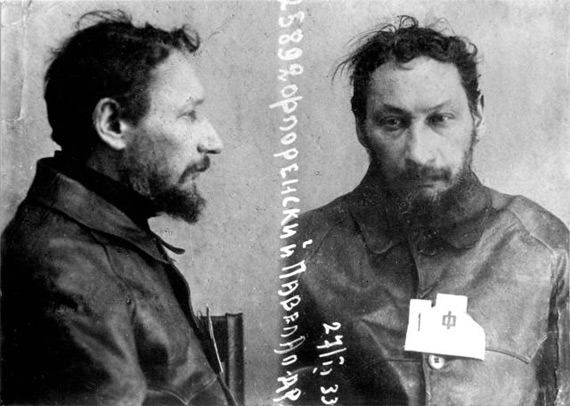

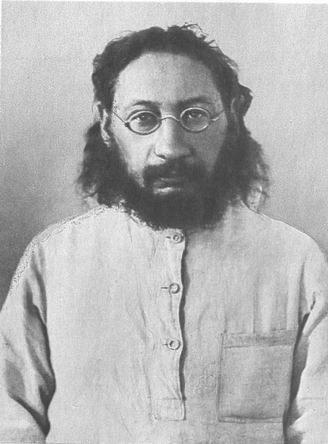

December 8 marks the 75th anniversary of the marytric death of Priest Paul Florensky, the eminent theologian, philosopher, art historian, and mathematician. On December 5, a memorial to all who suffered for the faith during the years of Bolshevik persecution was dedicated in Sergiev Posad. On the eve of Fr. Pavel’s anniversary, Pravmir spoke with his grandson, Igumen Andronik (Trubachev).

Russian universities

Vasily Rozanov said that Russians are formed less by universities than under the influence of their grandmothers and nannies.

This is Pushkin’s very beautiful conception of growing up. Fr. Pavel and his brothers and sisters had their own governess: Aunt Julia, their father’s sister. She, unlike her brother, kept her faith, reading the Gospels with her nephews and even taking the seven-year-old Pavel to receive Communion in Batumi – he writes about this in his memoirs. That is, she sowed the seed of religiosity in his soul.

But his father, again according to Fr. Pavel’s memoirs, took an intermediate position. As a man of action, he resisted the nihilism of the times. At one point he served as Deputy Minister of Communications in the Caucasus, but he found his bureaucratic duties burdensome. He loved practical work, which kept him from the temptations of nihilistic ideas.

But, typically for his time, he shared an enthusiasm for positivism. His father (Fr. Pavel’s grandfather) had graduated from the Kostroma Seminary, but later entered the medical faculty at Moscow University. At that time, in the early nineteenth century, some seminary graduates were sent to study at university. According to family tradition, however, Fr. Pavel’s grandfather went there in defiance: he had been intended for the theological academy, and even Metropolitan Philaret himself summoned him to try to persuade him to stay in the academy. He did not stay, but exchanged the priesthood for science – there was, as Fr. Pavel writes, a betrayal of the altar.

Did he leave the faith, or just reject the priesthood?

He was a military doctor in the Caucasus in a Don Cossack regiment. This way of life was described perfectly by Tolstoy in his stories about the Caucasian War. It was a peculiar way of life. Normal married life did not exist: Cossacks would have promiscuous relations with Circassians and then leave. They continued to live as freemen. Today it is accepted to extol the Cossacks, but have a look at And Quiet Flows the Don. Grigori Melekhov’s attitude to his Motherland is a copy of his attitude towards women: first one, and then another; first the Reds, then the Whites.

I don’t think that Fr. Pavel’s grandfather fundamentally parted ways with religion. Most likely, he simply became indifferent to it. And Fr. Paul’s father, as I have already said, was quite far from religion, but made peace with the fact that his son entered the theological academy after university. He was surprised and probably angry – he had wanted to see his son become a scientist – but not to the point of severing relations. It didn’t even lead to a quarrel.

Fr. Pavel’s mother was an Armenian who, I think, married his father in the Orthodox Church. They likely observed religious traditions of the everyday sort in their home. In the cities at that time, these traditions were reduced to receiving Communion once a year and celebrating Pascha. Not everyone even went to the Paschal services, but would instead celebrate it at home. They would break the fast, although they had only kept the fast for several days before Communion, which they usually received during Great Lent.

The revolution in the future Fr. Pavel’s worldview began in childhood, when one night he woke up to hear a voice saying: “Pavel, Pavel!” He wrote about this more than once.

Simplicity vs. simplification

Later he was attracted to the teachings of Tolstoy?

Yes, Pavel liked the moral side of this teaching as well as the idea of simplification. The desire for simplification was characteristic of various segments of the intelligentsia: from populists, Slavophiles, and revolutionaries up to the highest aristocracy. Tolstoy, in his philosophical works, constantly advocated simplification.

It hurt him very much that physical labor was considered the most valuable kind of work. No one is going to detract from physical labor, but is inventing airplanes, rockets, and atomic fuel really no greater than simply tightening screws? But among Russians, including those influenced by Tolstoyanism, the impression was created that the more primitive something was, the more worthy it was. Everyone knows where all this simplification led: to ball-bearings ruling the country.

Fr. Pavel loved simplicity (which is not the same thing as simplification) and therefore, for a certain time in his youth, he was attracted to Tolstoyanism by its moral side, but not by its religious ideas. By the 1920s he was already talking about the naivety of Tolstoy’s religious-philosophical reasoning.

In the years immediately after the Revolution he even debated with Anatoly Lunacharsky [first Soviet People’s Commissar of Enlightenment]?

This is one of the myths. He did meet Lunacharsky, but there were no discussions. Fr. Pavel also met Trotsky: when Trotsky was removed from all political positions he headed the department of industry and came to the All-Union Institute of Energy, where Fr. Pavel was working. They talked for all of five minutes, but in some books this passing encounter is inflated to the point of making him out to have some sort of connection with Trotsky, if not becoming friends with him. It was nothing of the sort. He always wrote exactly what he thought of Bolshevik ideology.

The right to criticize the gymnasium

Referring to the critical revolution, Fr. Pavel thought that ending the teaching of religion in school was the right thing to do. He also wrote that he developed intellectually not thanks to the gymnasium, but in spite of it. Why?

Rozanov was also critical of the gymnasium. What was so bad about the pre-revolutionary gymnasium? Probably the system of cramming, which did not plant any interest in, or love for, the subjects being studied. But the same could be said of any school. A great deal depends on the teacher. They had teachers of history and language arts that the entire gymnasium, including Fr. Pavel, remembered very warmly.

Cognition comes through comparison. Compared to what self-study gave to Fr. Pavel, the gymnasium seemed to him like an empty pastime. But not only Florenskys study in gymnasiums. In terms of ability and diligence, he far exceeded almost all his peers, for which reason he had the right to criticize the gymnasium. May God grant that today our schools would even approach such a level of education!

But that the classes in Law of God sooner turned people away from religion than strengthened them in faith, was something that not only Fr. Pavel wrote about, but many of his contemporaries as well – because the Law of God was being taught formally and dryly, with teachers requiring that the students cram. However, when priests in Sunday schools don’t give grades, but rather simply read the Gospels to the children and clarify what’s unclear, citing examples from modern life, then the children can aspire towards the Church.

A strictly formal approach to this subject, of course, is more likely to repulse them. But when Law of God classes were not only removed from schools, but children were forbidden to receive any kind of religious education, things became much worse than they had been before the Revolution – now this is obvious.

Marriage and monasticism: two hands

Fr. Pavel was churched under the guidance of monks. Did he himself never consider monasticism?

In his last year of university, he went with his friend Andrei Bely to their spiritual father, Bishop Anthony (Florensov). They asked his blessing to become monks, but Vladyka Anthony understood that this was most likely a matter of youthful enthusiasm. He advised the young men to finish theological academy first, and that things would then become clear. Fr. Pavel graduated, began teaching and then, through a sign from God, married and had five children. But he always had a great deal of respect for monasticism and, what’s no less important, monks always had respect for him.

At that time, “black” and “white” clergy were very often placed in opposition to one another. The rector of the Moscow Theological Academy, Archbishop Theodore (Pozdeevsky), even wanted to create a purely monastic academy, but he always treated Fr. Pavel with great respect.

This opposition, of course, was contrived. Marriage and monasticism are like two hands, and Russian monasticism has traditionally been connected with the world. Monks in the first centuries completely cut themselves off from the world, praying for the world and even guiding certain laypeople as spiritual fathers, but from a distance and remotely. They considered their main task to be praying for themselves and for the world.

This ideal is perfectly correct, but the conditions of life have changed. Today our monasticism is the vanguard: monks are cast wherever things are most difficult. So, for example, they are assigned to isolated rural parishes where a family priest simply could not survive.

Relatively little has been written about Fr. Pavel’s wife and children.

His wife, Anna Mikhailovna, was born in the village of Kutlovy Borki (which still exits) in the Ryazan Oblast. She was from the peasantry: her father was an estate manager and she herself completed the eighth grade and even taught for two years in her native village. But this was not the main thing. Rarely have I met such a wise and profound person as my grandmother. She became a bridge between generations, between those who were in the camps and our post-war generation.

The magnitude of her personality can be seen from the fact that she was buried (she died in 1973) by four bishops! Not even every priest gets buried by a bishop. And I, of course, owe a great deal to her.

Did all of Fr. Pavel’s children and grandchildren keep the faith?

Yes, and no one ever joined the Party – although, for instance, one of his sons, Kirill Pavlovich, survived the entire war, was promoted to captain, and took Berlin. Before every attack they would write applications to the Party, since they could be killed at any moment – but he never joined.

He was an excellent scientist, working in the Institute for Space Studies, yet he went to church whenever possible – usually when he came to Sergiev Posad. Many people in the cities at that time tried not to go to church, since this was kept track of and could get people in trouble.

The twentieth century will be saturated with occultism

Many criticize Fr. Pavel as being insufficiently Orthodox, even accusing him of a fascination with the occult. Where did this myth begin?

Well, for example, not only Fr. Pavel, but many other remarkable thinkers and theologians get their comeuppance in Fr. Georges Florovsky’s Ways of Russian Theology. Fr. Georges is very subjective and biased in his assessments. He wrote a remarkable book, but not an objective one.

It goes without saying that Fr. Pavel was never fascinated with occultism, although he did study this phenomenon and did say in his lectures to students at the academy that it was a very important thing to study, because the entire twentieth century would be saturated with occultism. And, indeed, as soon as atheism collapsed, there was mass enthusiasm for all sorts of occult things. And in the West, where state atheism didn’t exist, they also became fascinated with it throughout the entire twentieth century, just as Fr. Pavel had foreseen.

As you know, in nineteenth century Russia the intelligentsia and nobility grew more and more carried away with such mysticism. Fr. Pavel never judged people, but he did firmly uphold the truth. He understood that the Lord’s ways are inscrutable and that while one person might approach the truth directly, while another might come at it in a more roundabout way.

Andrei Bely, who in his youth wanted to become a monk along with Fr. Pavel, became an anthroposophist. In his letters to him, Fr. Pavel spoke very sharply about anthroposophy, but he neither rebuked Bely nor did he end their relationship. He was able to separate delusions from personality.

Does it follow from Fr. Pavel’s example that one should not be afraid of studying even spiritually dubious phenomena, if this is done for the sake of revealing the truth to people who have been deluded?

You know, not everyone needs to study this. One needs to have the ability and firmness not to be seduced, as well as love for the object of study. One might even compare knowledge to marriage. In order to study something properly, one needs to love it, one needs to see something good in it. Take the Greek mysteries and myths about the resurrected god Dionysius. One can simply dismiss this as paganism, saying that the pagans remained in darkness, or one can see glimpses of the idea of resurrection in pagan thought. A religious cult that is opposed to Christianity is one thing, and philosophical inquiry is quite another.

Occultism is a parasite on healthy human desires. Man has a spiritual need to commune with his departed relatives. This is the meaning behind prayer for the departed, memorial services, and the taking out of particles for the reposed at the proskomedia. This is the legitimate way, whereas occultism offers an illegitimate way, one leading to perdition, of communing with them outside the Church.

But the need to commune with one’s departed loved ones is natural. It follows that we should show someone with a need for occultism why the path he has chosen is wrong and dangerous. And this can be shown only if one has studied it.

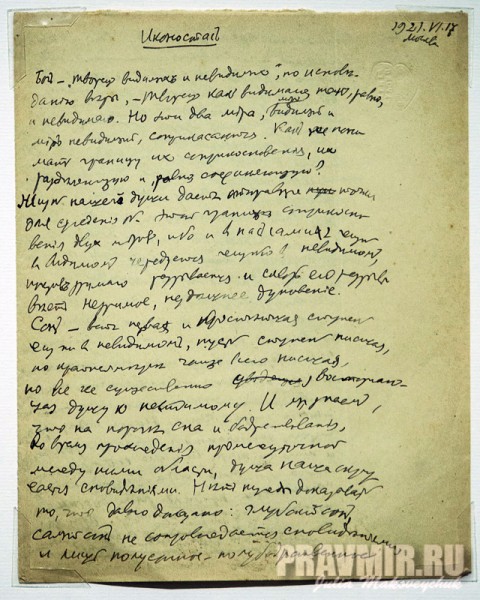

In my opinion, Fr. Pavel’s works are also valuable because, in an era of the cult of rationality, they show that there are other, higher paths to truth and that when the intellect rejects faith it cannot come to know truth.

The camp as path to Christ

Why has Fr. Pavel still not been glorified as a New Martyr?

The position of the Synod and Committee for Canonization is as follows: the question of canonizing someone who was accused of creating a non-existent counter-revolutionary organization and pleaded guilty will not be raised, even if he was later shot. This happens to be the case with Fr. Pavel. He was accused of creating a counter-revolutionary monarchist organization, to which he not only pleaded guilty but took the blame upon himself, saying that he was an ideologue.

He did this in an attempt to protect others but, according to the current position of the people entrusted with canonizations, the question of his glorification cannot be raised at the present time. This is the official position, but such attitudes change over time. Today many highly-respected church people support a different opinion: that surviving accounts of investigations should be taken into consideration, but should not be considered decisive.

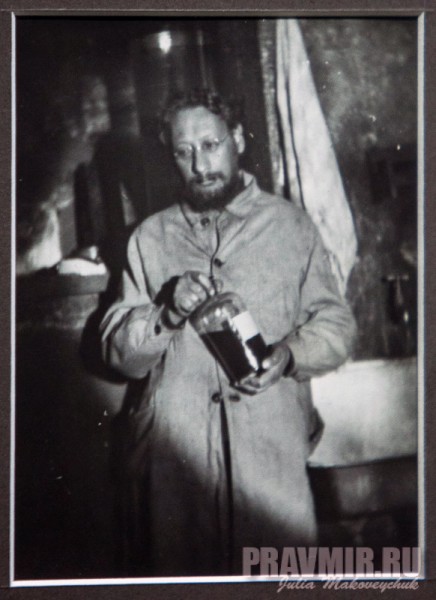

I think that Fr. Pavel Florensky has entered the host of martyrs. According to the recollections of people who were with him in the camps, he did not renounce his faith or his holy orders, but remained there patiently, uncomplainingly, and kindheartedly, preaching the word of God to those who were prepared to hear it. Moreover, while in the camp he was given the chance to travel to Czechoslovakia to join his family there, but he refused.

I think that Fr. Pavel Florensky has entered the host of martyrs. According to the recollections of people who were with him in the camps, he did not renounce his faith or his holy orders, but remained there patiently, uncomplainingly, and kindheartedly, preaching the word of God to those who were prepared to hear it. Moreover, while in the camp he was given the chance to travel to Czechoslovakia to join his family there, but he refused.

Following the Revolution, two of his spiritual daughters emigrated to Czechoslovakia, where one of them became a nurse for the elderly Czech President Masaryk, who knew and loved Russian culture. She apparently told him about Fr. Pavel, and he offered to appeal to the Soviet authorities to release Fr. Pavel and allow him to be visited by his family.

The family, which was living in Sergiev Posad, was informed that such a possibility existed. Anna Mikhailovna went to visit him in the camp, where she told him everything and then later wrote about all this to him in her letters. But in 1934 he refused. I don’t know of another case when a prisoner declined to leave a camp. This speaks to the fact that he regarded his stay there not as the result of political repressions, but as a path to Christ.

Interview conducted by Leonid Vinogradov.

Translated from the Russian