The end of the first week of Great Lent is approaching. This is one of the most grace-filled and difficult times in the life of each Orthodox Christian. For nearly the entire year we have led lives of vain concern, not heeding the Church’s constant appeal to “lay aside all earthly cares.” We have put off until later everything associated with God. Indulging our whims and completely giving ourselves over to “important” momentary concerns, we have not noticed the burden that every day weighs more and more heavily upon us.

Now that “later” has arrived, the time of Great Lent, and it can no longer be put off. At long last we can open to God our hearts that yearn painfully for Him – and immediately we will understand what a terrible burden we have been dragging along for the entire year, not stopping for a moment to be relieved of it at lest slightly. If even for a few days we shift our focus from our own daily worries to God, then it will be as if this burden had never existed, as smoke vanisheth and as wax melteth before the fire. Our bodies are filled with lightness, and our souls with joy. Only now, with tremendous delay, do we understand that we have deprived ourselves of communion with God. For the first time after a long winter we throw open the shutters that have blocked off our souls and we inhale deeply the grace-filled fresh air of spring.

But bright sunlight also flows inside along with the air. Suddenly we are horrified to discover just how much dirt and rubbish have accumulated within us. During the first four evenings of Lent the reading of the Great Penitential Canon of St. Andrew of Crete has opened to us 250 ways to look into our souls. With each such look an increasingly stark view opens before us: The whole head is in pain and the whole heart in grief; from feet to head there is no wholeness, nothing but wound, bruise, festering sore; it is not possible to apply plaster, or oil, or bandages (Isaiah 1:5-6). Before long one begins to despair.

But the very same doctor who painfully uncovers our festering wounds also offers us medicine. This becomes clear from the very first words of the last part of St. Andrew’s Canon, read on Thursday: “O Lamb of God, Who takest away the sins of all… I fall prostrate before Thee, O Jesus. I have sinned against Thee, be merciful to me… It is time for repentance. I draw near to Thee, my Creator. Take from me the heavy yoke of sin.” This is the oil that soothes our wounds: Christ, Who “slew the passions of my flesh through the Divine Cross.” This truth is frequently repeated in the divine services of Friday of the first week of Great Lent.

But stop! One must honestly admit that there is nothing new for us in these words; anyone who even occasionally goes to church will have heard similar words many times over during every divine service of the year. Christ, the Cross, the Resurrection, the Passion, Salvation: we employ these and many similar such words from church use in our daily lives as impersonal formulas and meaningless codes. If someone were to ask us how to be saved, we would automatically answer that Christ should become the center of our lives, or something like that. Let us give some thought to what it actually means for Christ to become the center of our lives. Perhaps this means placing a large icon in the icon corner? So we do so. Perhaps this means making use of His name more often and more loudly? So we do this, too. One can endlessly prolong the list of Orthodox cultural stereotypes. But in the depth of our souls we understand that following any of these stereotypes will not get us one step closer to Christ and, moreover, will not place Him at the center of our lives. Then how do we grow closer to Him? Have we returned to hopeless despair?

So, we have successfully neared the end of the first week. Four Complines with the Canon and two Presanctified Liturgies are behind us. So what lies ahead? One’s eyes as usual jump ahead to the next red-letter day on the calendar. Sunday is the Triumph of Orthodoxy. A triumph?! Wait a minute. We have just recognized the depth of our sinfulness and then remembered the existence of medicine that, as it turns out, we still have not taken – and now suddenly we are celebrating a triumphant victory? Have we already been healed? How and when did this happen? Perhaps this Triumph is not for us, but rather for the chosen saints? A deep sense of bewilderment remains, which does not dissipate even after the Sunday Liturgy.

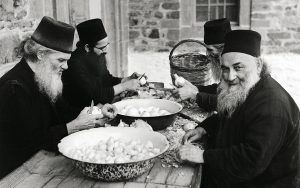

Alas, the majority of laity, due to their workload, can manage to go to church only a few times over the course of such an extremely important church week. One is forced to choose. And from year to year we jump from the unresolved questions of the beginning of the week immediately to the solemnity of Sunday. But the questions still remain unanswered. Where should we look? We return to the calendar: Thursday, Friday… Sunday. Yes, we have missed something… Ah, Saturday: “On this day of the Saturday of the first week of Lent, we celebrate with koliva the great miracle of the holy and glorious Great Martyr Theodore the Tyro.” Who is this Theodore the Tyro? What is koliva? What is this miracle?

Any more or less knowledgeable Orthodox Christian will know the basic story of the event celebrated on this Saturday. From the reading in the Lenten Triodion we know that in Constantinople Emperor Julian devised a trick by which to profane the Christians by ordering that blood sacrificed to idols be sprinkled on all the food sold in the market. Then the Lord sent the saint to Archbishop Eudoxius. He warned the bishop of the town governor’s plan, saying that they should eat a porridge made from ears of wheat taken from the uncontaminated grain storage. This dish was called koliva in the place the saint was from. Having inquired and learned that before him was standing one sent from God, the Great Martyrs Theodore the Tyro, the archbishop immediately followed his advice and prevented the Christians from being defiled.

Upon superficial reading, the plot seems more like a fairy tale, even a cartoon fantasy, in which Julian, like an unruly mouse, creates fine intrigues against Christians, as if they were Leopold the Cat. A superhero comes on stage, and everything finshes with a happy ending. But this story is worth making sense of.

If we examine it, we see that Emperor Flavius Claudius Julian (332-363 A.D.), nephew of Constantine the Great, Equal to the Apostles, was by no means a trivial figure. He was a very hardworking person possessed of a very high intelligence. Unlike the majority of Roman and Byzantine Emperors, before receiving the crown Julian had neither any military nor administrative experience. He devoted his life to obtaining a comprehensive education and conducting a philosophical search for the truth. When Julian was only five years old he had to endure the brutal murder of his father and older brother, who perished as a result of the intrigue of Constantius, one of the sons of St. Constantine, who was unworthy of the glory of his great father.

Constantine’s sons, anxious about the division of the spheres of influence within the Empire, jealously kept an eye on every possible challenger. Therefore Julian spent much of his life under house arrest or in exile. His life tragedy aroused hatred in him towards his uncle’s family and everything connected with it, including Christianity. On the other hand, as a result of the future Emperor’s classical studies, an admiration for ancient culture developed in him and, as a consequence, a romantic attachment to paganism, an adherent of which he became, first covertly and later openly. Therefore Julian has become known to history with the epithet “the Apostate.”

As the result of complex political conflicts, Constantius, who was left alone at the head of the Empire, was compelled to name Julian as his co-ruler, although initially this was no more than a nominal title. The Roman Empire, however, was too large for a single ruler; after a short time Julian was able to gain a firm foothold as Emperor of the West, while Constantius’ interests lay in the eastern territories. This would inevitably have led the cousins to conflict, had it not been for one more whim of fate: at the very beginning of the war between the rivals Constantius suddenly died.

Having become the sole Emperor, Julian was able to realize the political and religious ideals he had been nurturing his entire life. He considered the foremost among them to be the restoration of paganism as the dominant religion of the Empire and the eradication of Christianity. The young Emperor saw this as the key to restoring the former grandeur of the Roman Empire. But he was too smart simply to start a new wave of persecutions, as the pagan Emperors of past years had. Julian knew the history of the Empire well and, moreover, had been raised among Christians, for which reason he knew perfectly well about the exploits of the martyrs and that martyrdom only attracts more people to Christianity. Therefore he decided to act cunningly.

An example of such cunning politics was his attempt to revive the conflict between Orthodox Christians and the adherents of the Arian heresy. By the beginning of the reign of Julian the Apostate, the Arians had won an almost unconditional victory over the Church. The more active defenders of Orthodoxy were in exile. Emperor Julian the Apostate fully restored the rights of all Orthodox, among whom was Athanasius the Great, hoping to provoke a violent, and perhaps even bloody, conflict between the two sides. Christianity would be weakened and discredited as a result. He would have been very upset to learn that not only did he not achieve his goal but, by the Lord’s marvelous Providence, he laid the foundation for the revival of Orthodox theology, thereby helping to strengthen the beginnings of what we today celebrate as the Triumph of Orthodoxy.

Of course, thanks to his crafty mind, not all of Julian’s machinations were unsuccessful. Christianity would have suffered greatly had it not been for the Persian campaign of 363, during which the pagan Emperor was killed during a battle, not having completed even two years of his reign. According to legend, his last words were addressed to Christ: “Thou hast conquered, Galilean!”

But let us return to that failed trick of Emperor Julian to which our account is dedicated. Now, having discovered who Julian the Apostate was, we should understand that the story of sprinkling the food with blood was not simply a petty trick. The Emperor was well aware of all the intricacies of Christian belief, knowing that Great Lent was the time best suited for provocations against the Christians. He also knew that the Apostles had commanded Christians to abstain from pollutions of idols, and from fornication, and from things strangled, and from blood (Acts 15:20). Therefore the secret sprinkling of all the food in all the markets of the Empire’s capital with blood from animals sacrificed to the pagan gods was a precise and controlled strike.

We cannot know the entirety of this failed plan, but one can assume that after all the Christians had eaten the unclean food Julian would publically announce that they had defiled themselves on their very holiest days. This scandalous news would not only have dealt a strong blow to the reputation of the Christians, but it would certainly have caused all sorts of confusion, from discordance within the Church to social unrest. This in turn would have opened up room for the Emperor for further manipulations, right up to repression.

“But the all-seeing eye of God, knowing the cunning besetting them, and forever solicitous towards us, his servants, destroyed the lawless one’s infamous treachery.” The event we remember the day before the feast of the Triumph of Orthodoxy thereby visibly demonstrates our Savior’s concern and care for us. Moreover, this story teaches us how to fast reasonably. Sometimes in difficult situations it seems that we can choose between only two options: either to eat defiled food, as the Apostle says (cf. 1 Corinthians 10:25), or else not to eat at all. Both one and the other would have laid “grievous burdens” upon the people.

On the one hand, there was the temptation of succumbing to the imperial intrigues; on the other hand, there was the prospect of unbearable hunger. The majority of Christians would likely not have been prepared for either scenario. But the Lord, in His mercy and wisdom, offered a third way through the mouth of the Great Martyr Theodore the Tyro: porridge from boiled wheat, about which the majority would likely not have given thought, since they would likely not have thought of the raw product as an accessible source of food. But this dish was both nourishing and fasting.

One should pay attention to the fact that the outcome of this situation was determined not by supernatural intervention, but by the free will of the people of God. The most important figure in this story is Archbishop Eudoxius of Constantinople. Theodore the Tyro appeared to him in a dream. The bishop awoke on the following day and thought this over. He had three choices. First, he could pay no attention to this dream or consider it demonic in origin and therefore not binding.

Second, the bishop could have believed the Divine messenger, but for reasons of lack of faith approached the situation pragmatically and not disclosed his vision, either for fear of the Emperor’s wrath or of being ridiculed. But Eudoxius chose the third option: humbly fulfilling his obedience. Now imagine the depth of faith, the trust in the Lord, and the feeling of responsibility for his flock that must have filled this man who was neither ideal nor holy but, as the Triodion tell us, “unjust and un-Orthodox,” in order not to be tempted! Regardless of his sins, when it came to the most important thing he made the right decision.

But even after the archbishop’s correct decision, the situation might not have been resolved favorably. Let us conduct a thought experiment: imagine for a moment that all this happened in our days. At the beginning of Lent the Patriarch addresses us on television, saying that he had allegedly had a prophetic dream and, because of this, he asks us to restrict our menus for a certain time – and perhaps even until the end of Lent – to a single dish: porridge made of wheat. But for the vast majority of us porridge from unshelled wheat is hardly tasty! While it is difficult to predict just how contemporary Christian society would react to such a suggestion, it is likely that only a handful of people would immediately accept this obedience unconditionally and humbly. But just such a reaction was necessary to overcome the Emperor’s machinations and not to disgrace their faith in Christ!

As it turns out, the miracle here is not simply the appearance of the Great Martyr Theodore, but the fact that both the archbishop and all the Christians in Constantinople believed and accepted this appearance, as contrary to common sense as it might have seemed. The choice of Divine messenger did not play an unimportant role here. It would have seemed more natural to imagine an angel or a saint well-known to Eudoxius, such as an Apostle, in this role. But the Lord sent namely the Great Martyr Theodore. Why? We can easily discover the answer in his life.

Let us think about him more carefully. We see that Theodore was hardly a gray-haired old man, but rather very young. In those far-off days the age of recruits (and the saint’s epithet “the Tyro” in fact means “the recruit”) was often fifteen or sixteen, which today we would call the transitional age, with all the childlike naïveté, openness, purity, lofty impulses, youthful maximalism, active romanticism, and unbridled joy and bravado that go along with it. From his life we see with what zeal Theodore persuaded the other Christians to persevere to the end, how quickly and boldly he set fire to the pagan temple during his furlough and, finally, how straightforwardly and firmly he spoke with the judge.

Theodore came from a noble family. His father likely occupied a very high position. This is evidenced by the fact that senior municipal officials begged Theodore to offer sacrifices at least formally. Very little was required: to throw into the censer standing before the idle several grains of incense prepared by a priest or to eat a small piece of the gifts offered to the pagan deity. This ritual was in most cases only a small formality that bore more of a civic than a religious character. If we recall how many different kinds of formalities, sometimes of a strange or entirely incomprehensible nature, we carry out today, living under one government or another, we can say with absolute certainty that had we lived in those distant days we would have performed this ritual without giving it a second thought – just as the vast majority of those living in the Roman Empire did, among them many Christians. After all, when you do something that meaningless it is very easy to find a convenient excuse for it or to allude to the sinful weakness inherent in everyone, for which we later offer what appears even to ourselves to be genuinely sincere repentance…

Recall that Theodore’s martyrdom took place in 306 A.D., only a few years before the persecution of Christianity ended and then became the state religion. Generally speaking, in those days people already did not particularly believe in the pagan gods they had invented. The officials were willing to forgive Theodore even for the burning of the idol and for his defiant behavior while conversing with the judge. But the young soldier bravely maintained his faith.

For this reason the government officials found themselves in an entirely unpleasant predicament. On the one hand, they had to follow instructions and execute the young Christian, which meant incurring on themselves the wrath of his influential family; on the other hand, failure to comply with the requirements would mean being threatened with imprisonment at the very least. The judge tried to appeal to Theodore’s pride by contrasting Theodore’s position with that of Christ’s shameful death.

In his life of the martyr, St. Demetrius of Rostov writes:

“The torturer, astonished by St. Theodore’s courage and endurance, said to him: ‘Are you, the most abominable of all people, really not ashamed to place your hope on the Man named Christ, Who was Himself shamefully executed? Are you really so recklessly exposing yourself to torture for the sake of this Man?’

“The martyr of Christ replied thereto: ‘May such shame be the lot of me and of all who invoke the name of the Lord Jesus Christ!’

“Then the people began to cry out, demanding that St. Theodore’s execution be carried out more speedily.”

But the saint’s martyrdom was not a matter of youthful bravado, as it may seem at first. He was aware of the consequences of his words and actions. In his prison cell he prayed and glorified God; angels were present with him there. One of the last phrases spoken by the martyr to the judge was in response to the latter’s question: “What do you want: to be with us or to be with your Christ?” The martyr replied: “I am and will be with my Christ, and others can do as they please!”

Now it becomes clear why it was namely the Great Martyr Theodore who, roughly fifty years after his repose, appeared to Archbishop Eudoxius. Against the background of someone who sacrificed his life so as not to eat even crumbs of food sacrificed to the idols, the question of whether to sacrifice only the comfort of a pleasant meal for the same reason becomes clear. The archbishop understood this, as did, following his words, his flock in Constantinople.

Very often we read and absorb the life of a given martyr as if it followed a particular scheme that is reasonable and rational. Obsessed with our own reality, our own daily concerns, vanities, parties, and celebrations, we refuse to believe that someone could have renounced everything, simply and firmly saying “no” and accepting death. What fortitude and extraordinary faith, trust, and clarity one must have in order not to be frightened by threats and to sacrifice voluntarily what seems to us the most precious thing we possess: life! How many people today are capable of this?

For the majority of us, such a scenario is more likely to look crazy and absurd. We assure ourselves by saying that the Christians of the first century were not like us; to paraphrase Lermontov [adapted from the poem “Borodino” – Tr.], we can say: “Yes, there were people in a certain time who were not as the present generation… They were heroes, not us.” However, after reading the life of St. Theodore absolutely no impression of a superman is left. Yet it is also far from the contemporary image of the righteous person with his three main occupations in life: praying, fasting, and reading pious books.

Theodore had the same simple, common desires as any one of us. He certainly liked to enjoy himself and joke around, to eat tasty foods, to be with friends at some festival, to look at attractive girls, and perhaps even to dream of having a brilliant career and his own house and family one day. Perhaps he committed some sins. But at that single decisive moment all this immediately receded into the background and grew unimportant and, as it were, dull. In its placed remained only the radiant figure of Christ and the outer darkness around Him.

So is true Christocentrism only martyrdom? Let us review once more, recalling those whom we have mentioned: Emperor Julian, Archbishop Eudoxius, the anonymous Christians of Constantinople, and the martyr Theodore himself. No single one of them was either a perfect superhero or a perfect supervillain. They were all, generally speaking, ordinary people with their pluses and minuses.

Each one of them, however, was faced with a choice that would determine not only their own fate and chances of salvation, but also the fate and chances of salvation of other people. Like Theodore, Archbishop Eudoxius and his flock were able to discern the figure of Christ at the right time and to stand with Him. Julian, however, despite his erudition, was blinded by his hatred for his cousin, discerning the “Galilean” only in the last minutes of his life, when making a choice might already have been too late.

All of this clarifies that confusing question with which we began this article.

We recognize our sinfulness and know that we can be saved only through Christ. But how? This is simultaneously simple and difficult: Watch ye and pray, lest ye enter into temptation (Mark 14:38). We should always be in the state of prayerful expectation for that life choice that for some will happen only once, and for others more than once, that will determine our fate and that of the people around us.

Moreover, contrary to popular opinion, making this choice is not at all difficult. What is the real choice between the Light of Christ and darkness? The difficulty is in having the eyes of our heart sufficiently clean and unsullied by “beams” in order to recognize the Savior at the right moment against the background of a million inessential things and events. It is for this very reason that every year we try to carry out a general housecleaning of our souls during Great Lent.

Dear diligent readers, if you have read this far, you might pose the following reasonable questions: “Having written so much about the Great Martyr Theodore the Tyro, what specifically are you proposing? Not only have we attended one or even several services with the Great Canon and at least one Liturgy of the Presanctified Gifts and are intending to go to the Liturgy on Sunday, but now you are saying that we also need to go to church on Saturday?! Excuse me, but not everyone is able to take the entire week off, and without that it’s impossible. Moreover, this probably isn’t even served everywhere.”

In our family we long ago found an answer to this question. The commemoration of Theodore the Tyro has become one of our favorite family holidays. On this day we bake a special loaf of rye breast with a cross, symbolizing that Theodore, as we sing in the festal hymns, “rejoiced in the flames as though at the waters of rest, offering himself as sweet bread to the Trinity.” Of course we also make koliva: wheat porridge with honey are various dried fruits. It reminds us again, apart from the event we are commemorating, of words from the Gospel applicable to the holy Great Martyr: Verily, verily, I say unto you, Except a corn of wheat fall into the ground and die, it abideth alone: but if it die, it bringeth forth much fruit. He that loveth his life shall lose it; and he that hateth his life in this world shall keep it unto life eternal (John 12:24-25). We also prepare other fasting dishes. Before our meal we sing a moleben [supplicatory service] to St. Theodore with the reading of the canon, the text of which can be found on the Internet. Our son also looks forward impatiently for the end of the first week for this unpretentious but very warmhearted feast day.

Holy Great Martyr Theodore, pray unto God for us!

Translated from Russian.