In the Name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Spirit!

The Saturday of the fifth week of Great Lent is called the Saturday of the Akathist in the Church’s Typikon. The word “akathist” in Greek literally means “not-sitting” or “not-sitting hymn,” that is, a hymn during which one is not supposed to sit. The akathist was written no later than the sixth century; a tradition exists that its author was St. Romanos the Melodist.

In 626, in memory of the victory of the Greeks over the barbarians who besieged Constantinople and posed a threat to the lives of many, a kontakion was added to the akathist: “To Thee, the Champion Leader, we Thy servants dedicate a feast of victory and of thanksgiving as ones rescued out of sufferings, O Theotokos.”

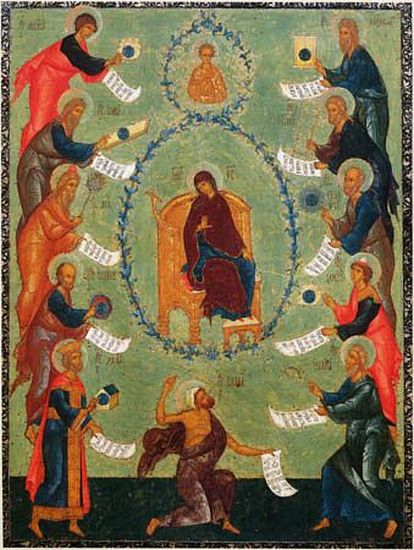

The Most Holy Theotokos is extolled in the akathist with the help of various metaphors, similes, and poetic images. The composition was written in Greek, and in the Greek original each of its lines corresponds rhythmically to the other lines; in many cases the endings of the verses rhyme. St. Romanos the Melodist, or another hymnographer whose name remains unknown to us, clothed the doctrine of the Most Holy Theotokos in entirely unique and very beautiful poetic form. People have been very fond of the akathist: over the centuries it has been read not only at divine services, but also during private prayer, both by monks and laymen.

At a much later period many other akathists were created that were modeled on this one: such as, for instance, the akathist to the Sweetest Jesus and the akathists to St. Nicholas and to other saints. But the one that was read today, in accordance with the Church’s Typikon, is the akathist in the true sense of the word. It is a remarkable and very profound composition that reveals the Church’s love of the Most Holy Theotokos and the Most Holy Theotokos’ love of the Church and of each one of us. Many Orthodox faithful read it when praying at home.

This year [2011] the reading of the akathist takes place on the day after the Feast of the Annunciation of the Most Holy Theotokos. This is by no means always the case, because the divine services of the Saturday of the Akathist are performed according to the Paschal calendar; Pascha, as is well known, occurs at a different time every year. This coincidence emphasizes in remarkable fashion the mystery of the Incarnation, of which the Feast of the Annunciation of the Most Holy Theotokos reminds us. It is with this mystery that the akathist begins: “An archangel was sent from Heaven to say to the Theotokos: Rejoice!”

Let us glorify the Most Holy Theotokos, the Mother of our salvation. Let us try to grasp the meaning of the words of this remarkable akathist, learning therefrom the Orthodox teaching of the Most Holy Theotokos. And let us ask that the Queen of Heaven – the Bride Unwedded and Joy of all who sorrow – never deprive of us her heavenly protection and intercession. Amen.

Translated from the Russian.

For those interested in a more detailed account of the historical circumstances under which the celebration of the Saturday of the Akathist was established, we offer the following learned essay by George Bitbunov:

The question of the origin and subject of the feast of the Saturday of the Akathist during the fifth week of Great Lent has generated no small number of conflicting points of view.

True, in the “Account of the Not-Sitting” [Povesti o nesedal’nom] (that is, of the akathist), included at the end of the Lenten Triodion, as well as in the synaxarion for the day, there is a clear indication: this commemoration was established in memory of the deliverance of Constantinople from the siege of the Persians and Avars in 626, during the reign of Emperor Heraclius. In addition, commemorations of two more miraculous savings of the Byzantine capital were added: from the Arabs in 672-678 (according to other sources, 669-675) and in 716. Meanwhile, none of the sieges mentioned correspond to the time of year the akathist is celebrated; their memory is included in the Constantinopolitan menologia under different months. Attempts have also been made to demonstrate that this feast was established in memory of the liberation of Constantinople from the Russians under Patriarch Photios in 860, but the arguments for this are not sufficiently convincing.

It must be admitted that the akathist to the Most Holy Theotokos itself gives very scant and extremely contradictory information about the chronology and meaning of the feast. Its text does not even hint at the liberation of Byzantium from invaders.

However, if one reads the akathist attentively, one cannot but notice that its thematic content, plot resolution, and subject reference are distinguished by an obvious duality. Archpriest Maxim Kozlov writes: “The historico-dogmatic content of the hymn is divided into two parts: the narrative, in which events connected to the earthly life of the Mother of God and the childhood of Christ are related, in accordance with the Gospel and Tradition (ikoi 1-12); and the dogmatic, which concerns the Incarnation and the salvation of the human race (ikoi 13-24).” [1]

In terms of appeal, beginning with the word “Rejoice,” the work is clearly addressed to the Theotokos. But many of its stanzas are addressed to Christ, for instance the eleventh (“Having become God-bearing heralds”), the twelfth (“By shining in Egypt”), and the thirteenth (“When Symeon was about to depart”). Moreover, the twentieth stanza strongly emphasizes that the akathist was composed for the glorification of Christ Himself: “Every hymn is defeated that trieth to encompass the multitude of Thy many compassions; for if we offer to Thee, O Holy King, songs equal in number to the sand, nothing have we done worthy of that which Thou hast given us who shout to thee: Alleluia.”

In terms of its form, the akathist belongs to a particular kind of ancient hymn: the so-called kontakia. In modern liturgical books only two stanzas have normally been preserved from these hymns, known by the names kontakion and ikos. The stanzas of the kontakia or ikoi are joined by an acrostic. Thus, in the akathist the alphabet serves as an acrostic, with the letter “alpha” beginning the stanza “An archangel was sent.” Thus, the first introductory stanza (prooimion), “To Thee, the Champion Leader,” is outside the alphabetical structure, which means that it might have been composed not by the author of the akathist, but by someone else. As some researchers believe, the given prooimion should be correlated with the above-mentioned “siege of Constantinople in the summer of 626 by the Avars and Slavs, when Patriarch Sergios of Constantinople circled the city walls with an icon of the Most Holy Theotokos and the danger was averted.” [2]

The text under consideration has two refrains: “Rejoice” and “Alleluia.” Such ambivalence is quite unusual and prompts one to advance the following supposition: one refrain, beginning with the word “Rejoice,” may be included only after those stanzas that contain glorification of the Theotokos, while “Alleluia” can be proclaimed after all twenty-four stanzas of the akathist, even without this glorification. This means that it cannot be ruled out that “Alleluia” was once the only refrain of the entire akathist, and “Rejoice” is a later element, inserted into the original wording. This is why the “Rejoice” refrain is not always organically connected with the general content of the akathist and obscures its basic idea and object rather strongly. The “Rejoice” refrains focus less on the person of the Theotokos than on the glorification of the Incarnation. This is expressed most distinctly in stanzas twelve to eighteen: while the first part of the each stanza is often an historical introduction to the “Rejoice” refrains, the latter part of each stanza mostly repeats and concludes them.

But, of course, the akathist also glorifies the “living temple” that served the mystery of the Incarnation: the Theotokos. It is for this reason that over the course of time it was found necessary to intensify glorification of the Mother of God in the akathist by introducing praise of her. The following well-known fact serves as an additional argument: the akathist has long served as the kontakion for the Annunciation, and one must assume that it was intended for this feast.

Thus, an analysis of the akathist compels one to search for the origin of the commemoration on Saturday of the fifth week of Great Lent in the feast of the Annunciation. Certain ancient rubrics concerning this commemoration also point in that direction. Previously it had not necessarily been tied to the Saturday of the fifth week. The commemoration on Saturday was, as it were, a forefeast of the Annunciation. Its connection with the Annunciation is seen from the fact that many of its hymns are taken from the service for that feast. That is, this commemoration leads one to a consideration of the transfer of the feast of the Annunciation.

Returning to our account of the historical background of the feast of the akathist, one must conclude that it, in accordance with the various arguments made by I. A. Karabinov, is connected not with the siege of Constantinople, but with Emperor Heraclius’ entire Persian war and, more precisely, with its successful finale for the Byzantines. [3] It is no accident that this event almost coincides by date with the feasts of the akathist and Annunciation. The paramia [Old Testament readings] (from the Prophet Isaiah) read during the fourth and fifth weeks of Great Lent witness to this; they, in turn, are related in content to the readings of Wednesday and Friday of Cheesefare Week.

Consequently, the historical memory of the end of the Persian war was celebrated along with the Annunciation: on the one hand, because the war ended on nearly that day; on the other, because the Theotokos was considered the Protectress of Constantinople, where this feast was first established. When the Council of Trullo resolved to establish the Annunciation on its own day, the commemoration of the war was allotted to the Saturday of the Akathist. Moreover, a shifting and restricting of the chronological strata took place over time, as a result of which the siege of Constantinople of 626 became current, inasmuch as it was the most memorable episode of the great war, which was conducted primarily outside the capital. The definitive establishment of the feast of the akathist on the Saturday of the fifth week of Great Lent took place quite late: only after the sixth century.

Author’s notes:

[1] Kozlov, Maksim, protoierei. Akafist v istorii pravoslavnoi gimnografii // Zhurnal Moskovskoi Patriarkhii. 2000. No. 6. C. 84. [Archpriest Maxim Kozlov, “The Akathist in the History of Orthodox Hymnography,” Journal of the Moscow Patriarchate. 2000, No. 6, p. 84.]

[2] Ibid.

[3] Karabinov, I. A. Postnaia triod’. Istorichesii obzor ee plana, sostava, redaktsii i slavianskikh perevodov. M., 2004. C. 63-64. [I. A. Karabinov, The Lenten Triodion: An Historical Survey of its Plan, Composition, Redaction, and Slavonic Translations. Moscow, 2004, pp. 63-64.]

Translated from the Russian.